The Secret Power Of Introverts

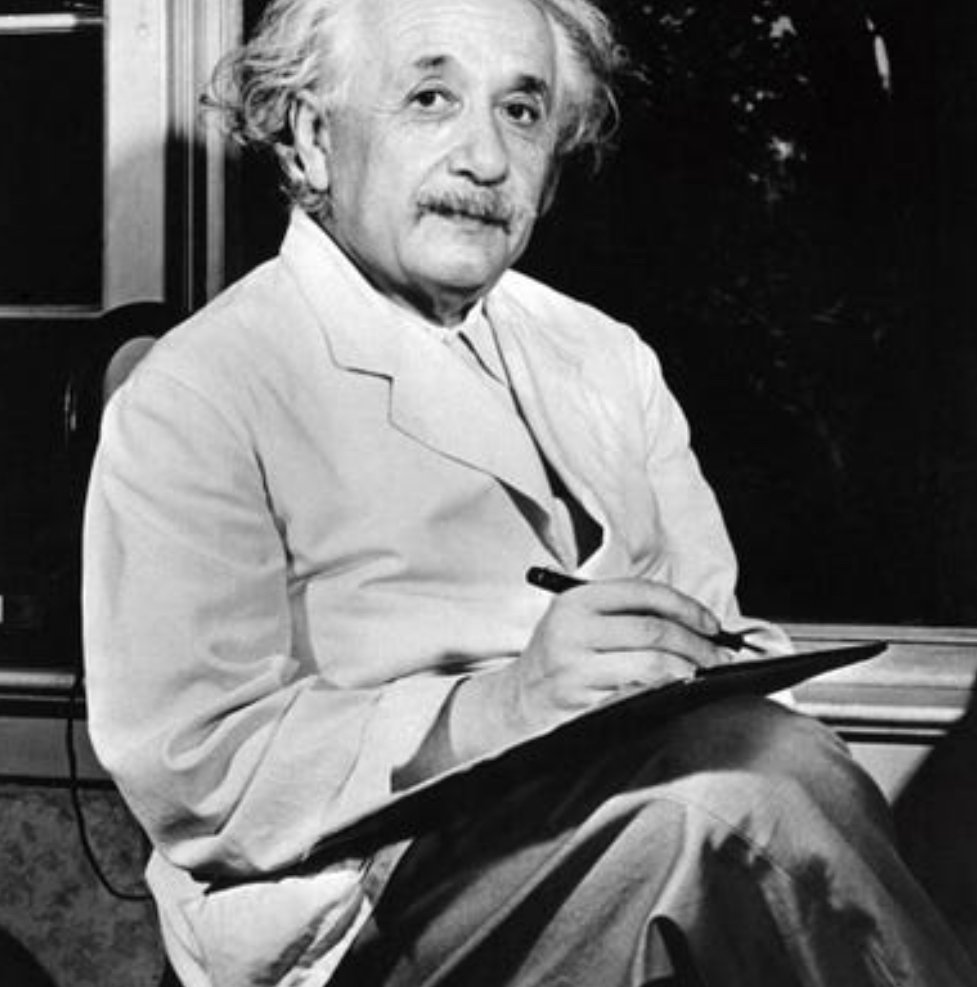

If you had to guess, what would you say investor Warren Buffett and civil rights activist Rosa Parks had in common? How about Charles Darwin, Al Gore, J.K. Rowling, Albert Einstein, Mahatma Gandhi and Google’s Larry Page? They are icons. They are leaders. And they are introverts.

Despite the corporate world’s insistence on brazen confidence–Speak up! Promote yourself! Network!—one third to half of Americans are believed to be introverts, according to Susan Cain, author of just released Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking. She contends that personality shapes our lives as profoundly as gender and race, and where you fall on the introvert-extrovert spectrum is the single most important aspect of your personality.

Introverts may make up nearly half the population, but Cain says they are second-class citizens.

“A widely held, but rarely articulated, belief in our society is that the ideal self is bold, alpha, gregarious,” says Cain. “Introversion is viewed somewhere between disappointment and pathology.”

The terms “introvert” and “extrovert” were first made popular by psychologist Carl Jung in the 1920s and then later by the Myers-Briggs personality test, used in major universities and corporations. By Cain’s definition, introverts prefer less stimulating environments and tend to enjoy quiet concentration, listen more than they talk and think before they speak. Conversely, extroverts are energized by social situations and tend to be assertive multi-taskers who think out loud and on their feet.

It was over the last century, says Cain, that society began reshaping itself as an extrovert’s paradise—to the introvert’s demise. She explains that before the twentieth century, we lived in what historians called a “culture of character,” when you were expected to conduct yourself morally with quiet integrity. But when people starting flocking to the cities and working for big businesses the question became, how do I stand out in a crowd? We morphed into a “culture of personality,” which she says sparked a fascination with glittering movie stars, bubbly employees and outgoing leadership.

In the last few decades, this “Extrovert Ideal” has transformed workplaces, says Cain. Independent, autonomous work that favored employee privacy was eroded and practically replaced by what she calls “The New Groupthink,” which “elevates teamwork above all else.” Children now learn in groups. Ideas are formed in brainstorming sessions. Talkers are considered smarter. Employees are hired for “people skills,” and offices are designed to be open and interactive.

Yet, according to Cain, it’s only worked to damage innovation and productivity. Research shows that charismatic leaders earn bigger paychecks but do not have better corporate performance; that brainstorming results in lower quality ideas and the more vocally assertive extroverts are the most likely to be heard; that the amount of space allotted to each employee shrunk 60% since the 1970s; and that open office plans are associated with reduced concentration and productivity, impaired memory, higher turnover and increased illness.

If we all lose in this situation, introverts lose more—with skills that are more likely to be overlooked and underappreciated. “Introverts living under the Extrovert Ideal are like women living in a man’s world,” says Cain. “Our most important institutions are designed for extroverts. We have a waste of talent.”

Cain is not seeking introvert domination. She acknowledges that big ideas and great leadership can come from either personality type. What she wants is a better balance and inclusion of different work styles. “In most job interviews, people say they are looking for people skills and emotional intelligence,” notes Cain. “That’s reasonable, but the question is, how do you define what that looks like?”

Furthermore, she believes that extroverted and introverted leaders excel in different areas and can learn from each other. Studies show that introverts are better at leading proactive employees because they listen to and let them run with their ideas. Meanwhile, extroverts are better at leading passive employees because they have a knack for motivation and inspiration.

While extroverted leaders could learn from their counterparts to take a more careful approach to risk and let others speak up, Cain says introverted leaders need to push themselves to be more social. She offers John Lilly, former CEO of Mozilla, as an example. He would force himself to walk the halls and make eye contact because he hadn’t realized how much it offended people when he didn’t greet them.

Ultimately, Cain believes, as a society, we are starving for stillness and need to turn down the noise. “It’s a very powerful thing to be quiet and collect your thoughts.”