Coming Out Under Fire: The Story of Gay and Lesbian Service Members

Two unknown American sailors in a photo booth. Image courtesy of Friends of the National WWII Memorial.

“Be invisible.”

Marvin Liebman, US Army Air Corps

At the age of 19, Marvin Liebman was drafted into the Special Services, US Army Air Corps during the waning years of World War II. Liebman and more than 9,000 American service members, however, eventually were given a section-8 ‘blue discharge’ for being homosexual. The 1994 documentary, Coming Out Under Fire, gives voice to the experiences of thousands of gay and lesbian service members who joined the military during World War II, a story that is largely ignored by historians and museums across the country.

The film is based on a book written by historian Allan Bérubé. However, it is important to place the film into its historical context. In 1993, the United States was debating the discriminatory “Don’t ask, Don’t Tell” policy regarding homosexuals in the modern military. The intense nation-wide debate resulted in congressional hearings where each member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff voiced supportive opinions of the policy and a reassertion of the policy by President Clinton. This film can and should be seen as not only a social commentary against the policy, but also an expression of the human cost behind such discrimination.

The film takes us back to World War II for a detailed look at the origins of the policy. We hear from nine veterans who, like all Americans, were asked to do their part. At the time, homosexuality was classified as a mental illness by the medical community. Mental illness was one condition that disqualified young people from service.

“Whatever attitudes we had about non-involvement immediately disappeared [after pearl harbor] and we became as much a part of the war effort as everyone else.”

Tom Reddy, US Marine Corps

The United States military, hoping to screen out mentally ill individuals, asked every potential service member questions on their sexuality. People who were gay and lesbian were forced to answer questions vaguely, or lie about their sexuality, in order to be allowed to serve; otherwise, they would run the risk of being sent home and branded as “sex perverts.”

By the middle of the war, the military sought new ways to target and expel homosexuals. Instead of charging individuals with sodomy, a court-martialed offense, the military began identifying suspected homosexuals as psychopaths. In other words, instead of charging service members with a crime of behavior or action, the military charged service members with a crime of being. Such a move created an efficient system of discrimination and prosecution of homosexual members of the military.

Service members who were persecuted by a section 8 blue discharge were purged from bases and units and sent to mental institutions and make-shift quarantined brigs where they suffered from isolation, depression, and humiliation, and were stripped of their rights and dignity.

“We felt liberated once we had discovered our own secret. We were gay.”

Tom Reddy, US Marine Corps

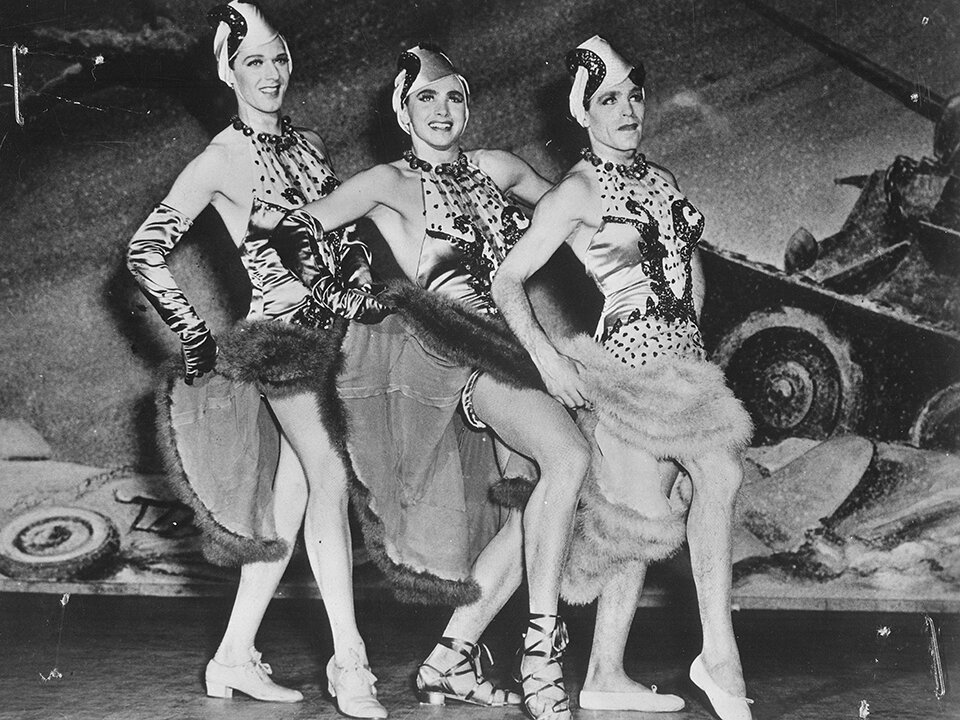

Despite the threat of persecution, gay and lesbian service members thrived during World War II. As with most young soldiers, many had never left their homes before and the war provided them an opportunity to find community, camaraderie, and, in some cases, first loves. These new friendships gave gay and lesbian GIs refuge from the hostility that surrounded them and allowed for a distinct sub-culture to develop within the military. Service members on every warfront enjoyed drag show entertainment; an entire gay lexicon was developed from the writings of Dorothy Parker; and eventually an underground queer newspaper emerged. The “Myrtle Beach Bitch” or “Myrtle Beach Belle” covertly shared news and stories between bases and units.

“This is the Army” was a GI show put on during World War II. Soldiers represented female characters in military plays and some homosexual soldiers found refuge from rigid gender roles. Image courtesy of Friends of the National WWII Memorial.

Many lesbians in the armed forces rose to positions of influence. Phyllis Abry, for instance, was featured in propaganda articles because she represented the ideals of a WAAC. Unknown to the Army, they also selected Abry’s lover as the other ideal WAAC to be featured together in the propaganda. The irony that the military selected two homosexuals to represent the ideal image of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps was not lost on Abry.

Phyllis Arby and Mildred, Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps. Image courtesy of Deep Focus Productions.

For many, World War II marked only the start of life-long struggles with their identity. The systematic purges of bases and units ripped apart the communities and relationships that had been developed over shared sacrifices. Blue discharges followed veterans their entire lives and made them ineligible for all veteran services. In 1953, President Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10450, that banned homosexuals from federal employment. Over 5,000 federal employees lost their jobs over accusations of homosexuality. These federal discriminatory actions drove LGBTQ people further into the shadows of society and emboldened law enforcement and politicians, who became more violent toward gay and lesbian citizens.

On June 28, 1969 police raided the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City. Patrons of the gay bar fought back and sparked a violent uprising that started the gay rights movement in the United States.

Gay and lesbian veterans of World War II became some of the first to fight military discrimination and blue discharges in the years following World War II. However, military discrimination became a cornerstone issue for the LGBTQ civil rights movement in the decades following the Vietnam War. The debate continued until 2010, when “Don’t ask, Don’t tell” was repealed and military service members could serve openly.

There is nothing more patriotic than doing your duty in the face of extraordinary odds. June, in particular, is a time that LGBTQ individuals defy the odds and celebrate diversity and pride. Don’t let the age of the film fool you: Coming Out Under Fire does a great service for our efforts to share a more complete history of the war that changed the world. My only hope is that organizations around the country commit to capturing the voices of gay, lesbian, and transgender veterans and that we find a place in our history to honor their service as well.

Clark and Buddies, US Army Air Force. Image courtesy of Deep Focus Productions

by Adam Foreman