The Military Finds Strength in its Diversity

Throughout history, America flourishes when it effectively harnesses the strength and innovation of its diversity. Black History Month offers an annual opportunity to reflect on the power and competitive advantage diversity provides to U.S. military forces.

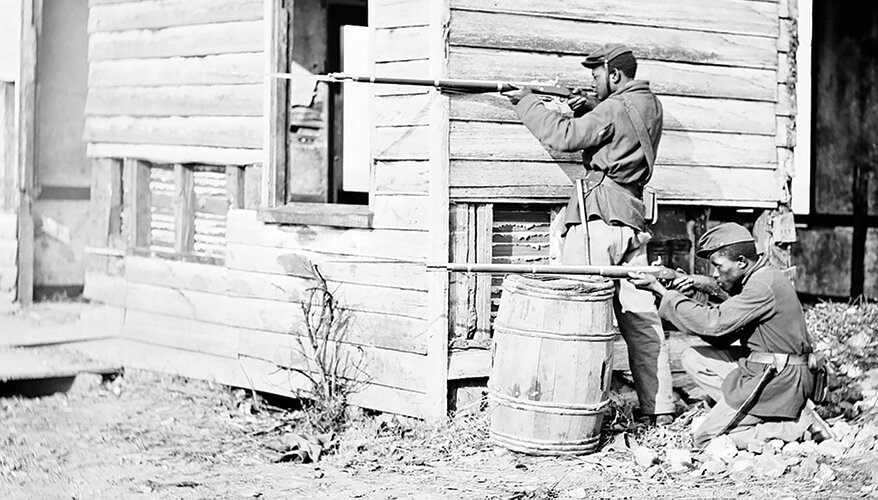

While there are many examples of individuals who blazed a trail for others, in the U.S. military the pathfinder among pathfinders is the Army’s buffalo soldiers, the men of the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments and 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments who enjoyed significant military success and paved the way for future integration of military units by women, African Americans and other minorities.

With the Union desperate for manpower, African Americans served honorably in the U.S. Army during the Civil War, mainly in United States Colored Troops Regiments. Post-Civil War, Congress directed the Army to recruit and field two black infantry regiments and two black cavalry regiments, resulting in these soldiers comprising 10 percent of U.S. Army end strength from 1870-1898.

Native Americans gave the 10th Cavalry Regiment the nickname “buffalo soldiers” in the Southwest and Great Plains, possibly because the soldiers fought so valiantly and fiercely the Native Americans afforded them the same respect as they did the mighty buffalo. Whatever the source, the nickname ultimately referred to all African American regiments formed in 1866.

Despite being paid as little as $13 a month, many African Americans enlisted in these regiments because military service offered an alternative to what they could expect in civilian society. Their main missions involved controlling Native Americans, capturing cattle rustlers and thieves and protecting settlers, stagecoaches, wagon trains and railroad crews — all missions they performed with distinction. Buffalo soldiers had the lowest military desertion and court-martial rates of their time, and more than 25 were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

While these regiments served mainly on the American frontier, earning a reputation for integrity and combat skill, some also fought in the Spanish-American War, Philippine-American War, and conflict on the Mexican frontier during World War I.

The men serving in these regiments demonstrated inspirational initiative, courage and patriotism in the face of significant prejudice, leaving a legacy of service that continues today.

In 1948, President Harry Truman issued an executive order eliminating racial segregation in America’s armed forces. The legacy of the buffalo soldiers helps ensure America fields much more effective, capable military forces because it leverages recruits from diverse, rich backgrounds. Different backgrounds lead to different perspectives and cognitive diversity, and cognitive diversity tends to generate better solutions and outcomes.

However, achieving this diversity can be very difficult. Leaders and managers like things to run smoothly, so, consciously or unconsciously, they tend to hire personnel with similar backgrounds and skills. These preferences get reinforced through job descriptions recruiters use to identify qualified applicants, while applicants who don’t share valued skills or backgrounds are less likely to get interviews.

However, abundant evidence demonstrates seeking out a specific “type” can lead to poor performance. Researchers at the University of Michigan found diverse groups solve problems more effectively than a more homogenous team. And while the Michigan study merely simulated diversity in a controlled setting, research into performance of commercial companies indicates diversity produces better outcomes.

A McKinsey report examining 366 public companies in a variety of countries and industries found more ethnically and gender diverse groups performed significantly better than homogeneous groups. The study found narrow backgrounds, experiences and outlooks limit the number of solution spaces the team can explore. At best, teams develop fewer ideas, and at worst, they run the risk of creating environments where inherent biases drive groupthink.

During the Iraq War, retired Army Gen. Stanley McChrystal, former Joint Special Operations Command commander, identified lack of cognitive diversity as a problem and implemented policies to break down barriers within his task force. As he explains in his book, Teams of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World, he had a diverse group of Navy SEALs, Army Special Forces and other elite units under his command. Yet despite their individual prowess, their group identities made it hard for them to integrate their efforts and collaborate effectively.

He responded by implementing strategies to drive integration and inclusion, expanding cognitive diversity. He upgraded the importance of liaison officer positions, incentivizing highly skilled operators to volunteer for embedded key positions in other units. For example, a commando would spend six months in an analyst unit while an analyst embedded with commandos. Over time, internal silos broke down and the blended group identity and culture of the entire task force drove positive mission outcomes.

We must continue to relentlessly pursue diversity to realize better outcomes. U.S. national security needs access to every idea and innovation to ensure it operates with a competitive advantage in every scenario. Embracing and strengthening inclusion helps ensure America’s military remains ready and able to excel in any contingency.

From the buffalo soldiers to ongoing efforts to recruit underrepresented segments of the U.S. population, the National Defense Industrial Association continues to honor all Americans’ service with its strategic focus on workforce and innovation. NDIA will continue to look for ways to honor the rich history and heritage of all Americans who have courageously served in the nation’s military.