Issue at a Glance: LGBTQ Employment Discrimination

Discrimination in the workplace and in hiring practices against LGBTQ people continues to be commonplace in the United States today. A 2017 Harvard opinion survey of LGBTQ Americans found that 90% believed that discrimination against them existed in the United States today. 59% said that where they live, they are less likely to be afforded employment opportunities because they are part of the LGBTQ community. One in five stated that they have had difficulty when applying for positions. Unemployment rates among transgender respondents are three times higher than the general population, according to data from the National Center for Transgender Equality.

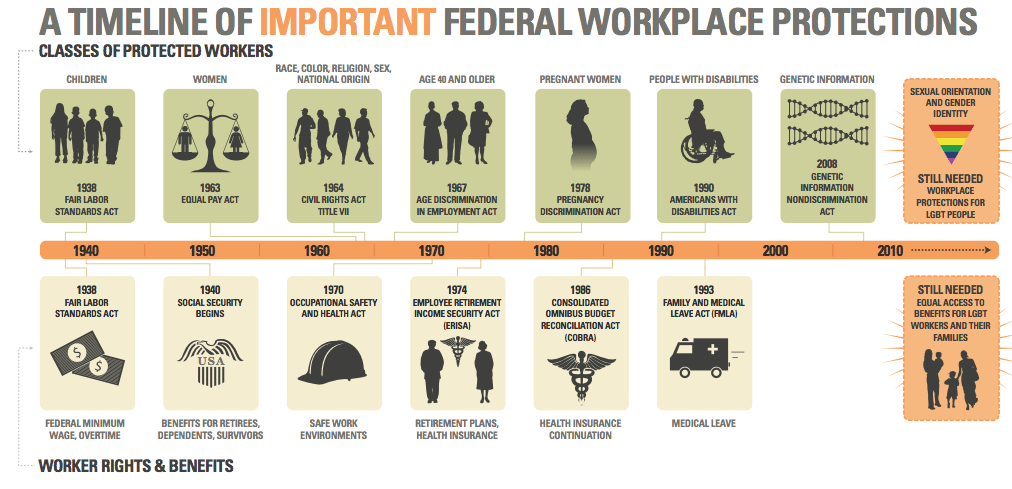

Without a federal law protecting LGBTQ Americans in the workplace, non-discrimation ordinances vary significantly by locality and the extent of the protections. Protections against discrimination on the basis of both sexual orientation and gender identity in both public and private employment is present in 20 states and the District of Columbia. Other states have protections but only in public employment, or they have protections only based on gender identity, or other varying combinations. In 2017, 17 states had no protections at all on the state level.

Source: Movement Advancement Project & The National LGBTQ Workers Center

Many cities and counties in states without protections have created laws and ordinances of their own to protect their LGBTQ populations, but three states have laws that have explicitly forbid local governments from passing such laws: Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina. This stripping away of a city’s ability to pass an ordinance in a specific area is known as preemption (a common tactic to erode rights in other areas, including pay equity, minimum wage increases, etc.). Tennessee was the first to pass a law barring cities from passing anti-discrimination ordinances in 2011. Arkansas followed suit in 2015 and in 2017, the Arkansas Supreme Court overturned Fayetteville’s anti-discrimination ordinance, thus cementing the policy for the rest of the state. And of course, North Carolina passed the infamous HB2 in 2016, which prompted national statewide boycotts and inspired a wave of LGBTQ candidates to come out and run.

LGBTQ elected officials have been on the front lines of employment non-discrimination and LGBTQ-inclusive fair pay. For instance, Rep. Jared Polis, who voted in favor of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009, and they still are, such as Maine state Senator Justin Chenette, who reflected many Americans’ feelings towards erosion of rights: “LePage’s [Maine’s Governor] decision to challenge a fed court’s ruling that protects gay Mainers from workplace discrimination is taking us backwards. Granting corporations the ability to fire someone simply because of who they love, ignores work ethic, skill set, education, & attitude.”

Despite the fight ahead, in 2018 alone there’s been great progress. Seven states passed and/or had court rulings expanding protections to include gender identity, and two more have included sexual orientation as a protected class. New Jersey’s Fair Pay Act of 2018 adds sexual orientation and gender identity to a law that is already the most progressive fair pay legislation in the country, as it ensures that companies have to pay women and other protected minorities backpay if one can prove they were paid less than others. In California, Senator Ricardo Lara authored Senate Bill 396, otherwise known as the Transgender Work Opportunity Act upon its signing into law by Governor Jerry Brown, which expands sexual harassment training to include content on gender identity and sexual orientation, requires employers to display a poster with information about transgender workplace rights, allows workforce development boards/agencies to target programs with transgender inclusivity aims, and allows appointments to the statewide Workforce Development Board of those whose work is focused on the LGBTQ community. 2018 brings the number of states with no employment protections, on either the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity, down to 12.

Source: Movement Advancement Project & The National LGBTQ Workers Center

At the LGBTQ Victory Institute, our mission is to provide resources and help build a pipeline of LGBTQ elected officials at all levels of government. In a literal sense, LGBTQ candidates are requesting the voters to hire them. Elected officials work for their constituents, and many of these people fear losing the ability to work themselves due to being a part of the LGBTQ community. Our community needs fair pay legislation on both the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity on the federal level. Even though the number of states without such protections continues to fall, no doubt will there be holdouts who refuse to pursue equality and fairness unless prompted to by the federal government.

by Logan Graves