3 Situations Where Cross-Cultural Communication Breaks Down

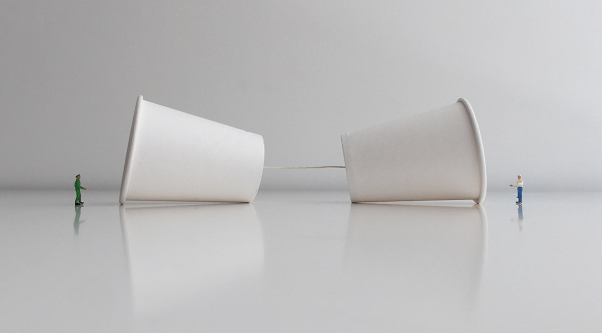

The strength of cross-cultural teams is their diversity of experience, perspective, and insight. But to capture those riches, colleagues must commit to open communication; they must dare to share. Unfortunately, this is rarely easy. In the 25 years we’ve spent researching global work groups, we’ve found that challenges typically arise in three areas.

Eliciting Ideas

Participation norms differ greatly across cultures. Team members from more egalitarian and individualistic countries, such as the U.S. or Australia, may be accustomed to voicing their unfiltered opinions and ideas, while those from more hierarchical cultures, such as Japan, tend to speak up only after more senior colleagues have expressed their views. People from some cultures may hesitate to contribute because they worry about coming across as superficial or foolish; Finns, for example, favor a “think before you speak” approach, in stark contrast to the “shoot from the hip” attitude that is more prevalent among Americans.

Communication patterns may also make it difficult for people to participate equally in brainstorming sessions. Brazilians, for instance, are typically at ease with overlapping conversations and interruptions, viewing them as signs of engagement. But others, accustomed to more orderly patterns of communication, can feel cut off or crowded out by the same behavior.

The fix: To ensure everyone is contributing, leaders of cross-cultural teams should establish clear communication protocols. A classic tactic, when soliciting ideas or opinions, is to go around the table (or conference line/video chat screens) at least once so that everyone has a chance to speak. Encourage exploration by asking open-ended questions and keeping your own thoughts to yourself at first. Recent research on teams of Americans and East Asians shows that such tactics result in dramatically more even contributions: Instead of taking five times as many opportunities to speak and using nearly 10 times as many words as their Chinese, Japanese, Korean, or Taiwanese colleagues, Americans took just 50% more turns and spoke just 4% more words when an inclusive team leadership approached was used.

If equitable air-time or interruptions are the problem, try adopting a “four-sentence rule” to limit your most loquacious team members, or insisting on an obligatory gap between two people’s comments, to give everyone time to respectfully jump in.

Surfacing Disagreement

Comfort with public disagreement is another big source of conflict on cross-cultural teams. Members from cultures that place a high value on “face” and group harmony may be averse to confrontation because they assume it will descend into conflict and upsets group dynamics – in short, social failure. In other cultures, having a “good fight” is actually a sign of trust. People from different parts of the world also vary in the amount of emotion they show, and expect from others, during a professional debate.

When, for example, people from Latin and Middle Eastern cultures raise their voices, colleagues from more neutral cultures can overestimate the degree of opposition being stated. On the flip side, when people from Asia or Scandinavia use silence and unreceptive body language to convey opposition, the message is often lost on more emotionally expressive peers.

The fix: To encourage healthy debate, consider designating a devil’s advocate whose remit is to consider and prompt discussion of the challenges associated with different propositions. The role can be rotated across agenda items or across meetings, so everyone becomes more comfortable in it. Another option is to spread the same responsibility by asking everyone to offer pros and cons on a particular course of action so people feel free to argue both sides, without getting locked in to positions they feel obliged to defend.

Giving Feedback

Constructive criticism is an essential part of global teamwork; it helps to iron out some of the inevitable kinks – relating to punctuality, communication style, or behavior in meetings – that aggravate stereotypes and disrupt collaboration. But feedback can be its own cultural minefield. Executives from more individualistic and task-oriented cultures, notably the U.S., are conditioned to see it as an opportunity for personal development; a “gift” best delivered and received immediately even if it’s in front of the group. By contrast, people from more collectivist and relationship-oriented cultures may be unaccustomed to voicing or listening to criticism in public, even if the team would benefit. For face-saving reasons, they may prefer to meet one-on-one in an informal setting, possibly over lunch or outside the workplace.

If they come from hierarchical cultures, such as Malaysia or Mexico, they may not even feel it is their role to offer direct feedback to peers and instead deliver it to the team leader to convey. The words people choose to use will vary greatly too. Executives from low-context cultures, such as the Netherlands, for example, tend to be very direct in their corrective feedback, while those from high-context cultures, such as India or the Middle Eastern countries, often favor more nuanced language.

The fix: Leaders should encourage members of cross-cultural teams to find a middle ground. You might coach people to soften critical feedback through positive framing and/or by addressing the whole team even when sending a message to just one person. For example, if time-keeping is a recurrent issue, you might say “I always appreciate it when we’re all synchronized and we can make the most of our time together.” It’s also important to model the right behavior and show that you expect and appreciate constructive criticism yourself. A good starter question is: “Reviewing our meeting, what should I do more of, less of, and the same of?”

Beyond these quick fixes, teams need to pre-empt conflict on cross-cultural teams by developing a climate of trust where colleagues always feel safe to speak their minds. If you discuss potential problem areas early and often, you’ll be well on your way to leveraging your group’s diversity, instead of seeing your progress and performance stalled by it.