Service Members Speak Out on Difficulties of Transitioning to Civilian Life

“I’m sure you’ve shot at people,” one of Michael Henderson’s classmates said. “Why don’t you tell us what death is about?”

It was a classroom debate, on a liberal American campus, about the use of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Henderson was the only person in the class who’d served in the military — four years in the Marine Corps, serving in Iraq. All eyes turned to him.

His classmate’s request was a hard one. How do you explain death on the battlefield to someone who’s never been on one?

“There is this misunderstanding that civilians have,” Henderson said. “When you serve you don’t always expect to shoot someone, but you always know there’s a possibility you can shoot at someone.”

For Henderson, the hardest part of his transition was trying to relate to those around him. The structure of college gave him a good place to think through his own experiences in Iraq and to recognize that many civilians will never understand those experiences. But he notes that the transition to civilian life has been much more difficult for some of his peers who aren’t able to create a separate life from the Marine Corps.

“You get used to everything being in lockstep and then all of a sudden you have to create that routine for yourself,” he said. “I think that’s where a lot of friends that I’ve had from the Corps have fallen. They didn’t have something to rally behind — for me it was school, for others it may have been a child.”

For many veterans, the transition process could be improved by focusing on broader life skills.

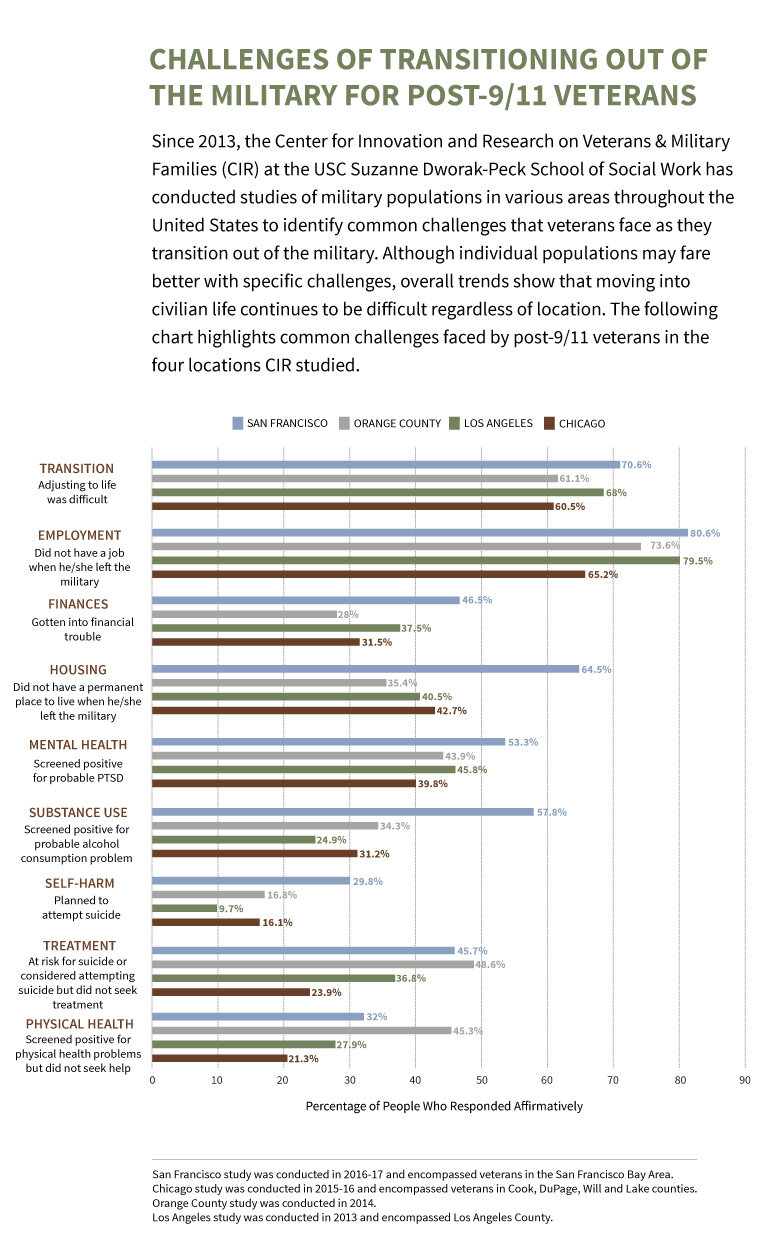

According to the Department of Defense External link , about 1,300 military service members, spouses and children transition into civilian communities each day. And while a series of studies External link conducted by USC’s Center for Innovation and Research on Veterans and Military Families (CIR) at the Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work show that the majority of veterans look favorably on their military experience, the majority also report having difficulty adjusting to civilian life, which can lead to larger problems such as joblessness, homelessness and untreated mental health conditions.

Sara Kintzle, research associate professor at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, helped to conduct the surveys. In general, she said, “What you see is a lack of preparedness for transition and a lack of understanding of expectations for what life is going to be like after the military.”

Service members separating from the military go through a Transition Assistance Program designed to help prepare them with a skill set to succeed in the next phase of their life. These programs focus on hard skills such as writing a resume, interviewing for potential jobs, and writing cover letters. Henderson’s skills training program lasted just one day.

In contrast, Matthew Suber, a veteran who was active duty in the U.S. Air Force for more than five years and separated as a captain, had a week of transition training.

Even so, Suber said the Transition Assistance Program fails to address one of veterans’ most pressing needs — how to translate what they have accomplished in the military into something of value for friends, classmates and particularly employers.

“When most military members are thinking about transitioning, what they really want to hang their hat on is all of the great things that they did,” Suber said. “But most employers say, ‘OK that’s great, but tell me what you can do. What are the skills that you have and how can you turn those into value adds for me and my company?’ That is where a lot of military members and myself included really struggle at the initial part of the transition.”

Henderson agrees.

“People aren’t going to understand what you did and you’re not going to be able to really explain it to them because you still haven’t rationalized it yet,” he said.

People leave without a job, without knowing where they are going to live, without understanding how much rent is or how much a deposit costs.

The effectiveness and usefulness of these programs may also depend on a service member’s experience in the military.

In Suber’s program, some of the participants were in their 40s, while others served four years and were leaving the military while still in their 20s. The needs of these groups weren’t necessarily the same, he said, yet they were forced into the same curriculum. He pointed out that his program did a good job of providing resources that were available to him as a veteran, but that not everybody in the room was absorbing the information in the same way.

“I was really frustrated because I would watch these 22-year-olds glaze over all of the resources that are available,” Suber said. “People miss out on resources or benefits because they don’t know how to apply. They don’t know if it’s something they should pursue.”

For many veterans, the transition process could be improved by focusing on broader life skills.

“People leave without a job, without knowing where they are going to live, without understanding how much rent is or how much a deposit costs,” Kintzle said.

Henderson said something as simple as learning how to balance a checkbook could help veterans avoid making bad decisions that lead them into financial trouble.

“It would have been nice to have a course on what real life is like on the outside,” he said. “Life is going to be hard and you are going to have to work just as hard if not harder. And the consequences of your actions now aren’t that you just get yelled at by someone in your platoon.”

CIR is scheduled to host the State of the American Veteran Conference on September 28 and 29, where professionals from corporations, community organizations and philanthropic foundations will examine effective methods to help veterans and their families through the transition process into civilian life.

“When we think about how we want to improve the lives of service members, veterans and their families, we want to prevent challenges from occurring,” Kintzle said. “A great place to start is at the transition point — when these people are coming into our communities, when we can get to know them and understand their needs and address their needs.”

The conference will look specifically at the unique transition experiences of five groups: combat veterans, student veterans, women veterans, Guard and Reserve service members, and children and families. Building from the data that CIR has collected along with the expertise of leaders from across the country, attendees will draft policy recommendations for how to make the country more military-friendly as veterans separate from the military and return to civilian communities.

“This conference is more than a conference — it’s a movement,” Kintzle said. “It’s a movement toward collaboration, toward coming together, sharing ideas and knowledge, challenging one another, and it’s all for the common purpose of improving the lives of people who have served in the military.”

by MSW