8 of the Biggest Misconceptions People Have About Native Americans

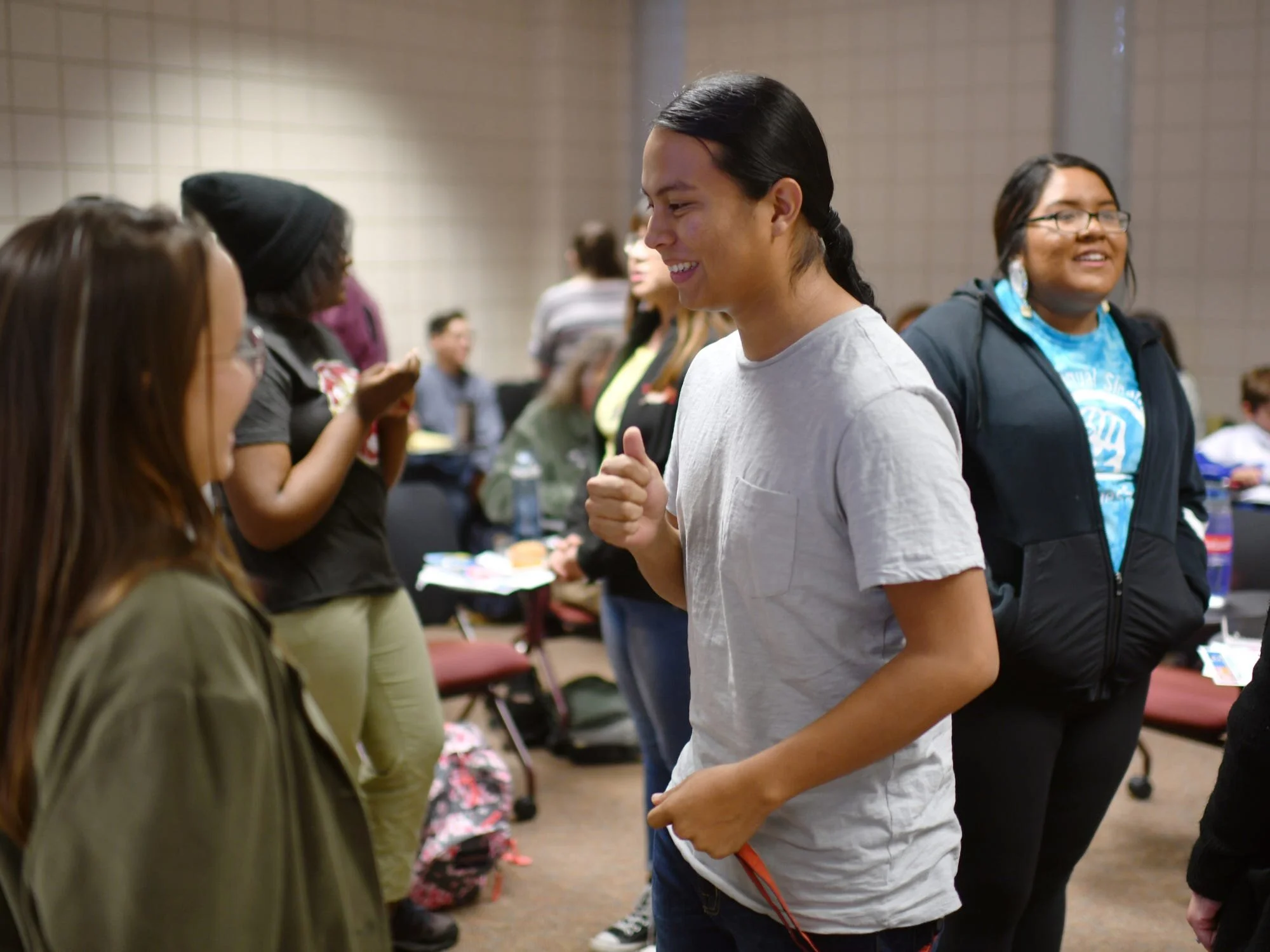

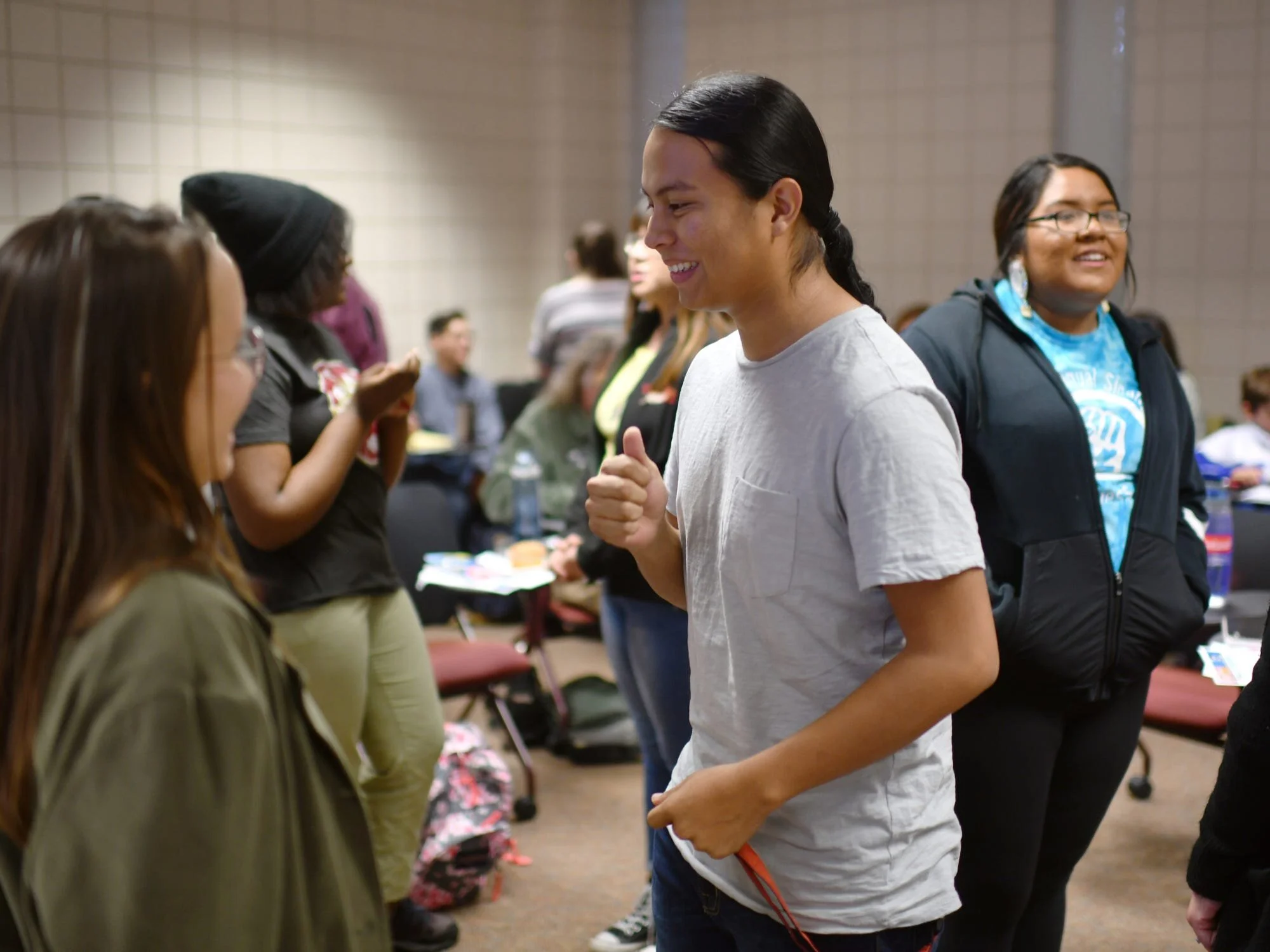

People participating in the Lakota Language Weekend, a crash course on Lakota language and culture, at the University of Denver in 2018.

Hyoung Chang/The Denver Post via Getty Images

As one of the few Native American people in the entertainment industry, I'm used to being asked bizarre questions about my culture.

Many people seem to think that all Natives live in teepees and look like caricatures from the 1700s.

Here are some of the weirdest and wildest misconceptions people have about being Native American today.

As one of the very few Native American people working in the entertainment industry, I'm used to being asked bizarre questions about my culture and upbringing.

Growing up on the Tulalip Indian Reservation in Washington state, I was ill-prepared for how little your average person knows about Native issues.

For context, according to a recent study by the Native run nonprofit IllumiNatives, 87% of United States schools don't cover Native American history beyond 1900. And that fact isn't more apparent than when a grown adult — who went to college and should really know better — asks me if I was born in a teepee.

To head some of these questions off at the pass, I'm here to clear up some of the weirdest and wildest misconceptions people have about being Native American in the 21st century.

We weren't all born In teepees.

Artur Widak/NurPhoto via Getty Images

You'd think I wouldn't need to tell people that an entire race of people wasn't born in teepees or doesn't currently live in them. But if the multiple times I've been asked if I was born in a teepee is any indication, it's very important that I address this question first.

Teepees were mainly used by tribes located in the Great Plains region of the United States, as well as in the Canadian Prairies. As members of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, based in and around southern Washington state, my people most likely didn't live in teepees. We traditionally lived in longhouses, which are large homes made out of cedar and shared by half a dozen to a dozen families.

So the real question is, "was I born in a longhouse?"

The answer to that question is no. It's 2020. I was born in a hospital in a big city, like you probably were. Why would you ask me such a weird question?

We don't all look like a caricature from the 1700s.

People participating in the Lakota Language Weekend, a crash course on Lakota language and culture, at the University of Denver in 2018. Hyoung Chang/The Denver Post via Getty Images

As a lighter-skinned Native with short hair, I'm regularly asked by non-Natives if I'm "really Native."

You know when I wasn't asked this question? When I had long hair.

Natives are often forced into a small cultural box by non-Natives, which severely limits how we're allowed to present ourselves to claim our Nativeness. Women have to look like Disney's Pocahontas, who, if you aren't already aware, is a literal cartoon character. Men have to look like the crying Indian from those old anti-littering PSAs, who, by the way, was played by an Italian guy.

Native film and television actors often lose acting roles for not fitting into this stereotype, and many are literally painted on set to make their skin appear more "red" for the camera.

Are there Natives out there who have long hair and wear traditional buckskin? Sure. But there are Natives with hair of all lengths and colors and skin in any tone imaginable. Just because someone doesn't look like an extra from an old John Wayne movie, with flute music playing every time they talk, a stoic expression always stuck to their face, and a best friend who is a literal eagle, that doesn't make them more or less Native.

We're not all the same tribe.

AP/John Locher

I am an enrolled member of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe. This is not to be confused with the Cherokee Nation, the Nez Perce tribe, or the Lakota tribe. In total, there are 570-plus federally recognized tribes in the United States, hundreds more at the state level, and a ton more that are not federally recognized.

Tribes have their own cultures, languages, aboriginal lands, traditional outfits, and everything in between. The cultural differences from one tribe to another could be as big as the cultural differences between the United Kingdom and Egypt.

To assume that all Natives wore loincloths or buckskin, or hunted buffalo, or whatever your elementary school teacher told you about Native American people while you made a construction-paper headdress the week before Thanksgiving is probably wrong, and in the case of the headdress, more than a little racist.

There's no such thing as being 18% Cherokee.

Sven Hoppe/picture alliance via Getty Images

I refer to myself as "enrolled Cowlitz." That means that I am "on the books" with the Cowlitz Indian Tribe — I have a tribal ID card and an enrollment number. My tribe's office can track my lineage back to which original Cowlitz family I belong to. I have a biological tie to being Cowlitz, but I also am an enrolled member of my tribe in the same way that you are a citizen of a state or country.

Tribes are, quite literally, "domestic dependent nations" operating within the US. The tribe is the only group that controls the requirements for enrollment in that tribe, and every tribe has different rules when it comes to enrollment.

Some tribes require for enrollment a certain "blood quantum," which is a controversial measure of how Native American you are based on how far removed you are from your "full-blooded" ancestors. Blood quantum laws are problematic for a whole slew of reasons I won't get into here, and contribute to a belief that the US government views Natives as less than human. (The only beings the government measures in blood quantum are "dogs, horses, and Indians.")

Much like becoming a citizen of a country or the resident of a state, once you're a member of a tribe, you are effectively 100% a member of that tribe. To say that you're ".05% Cherokee" because a DNA test told you so is the equivalent of telling someone from Texas that you're ".05% Texan," which would be ridiculous.

Some Natives love the term 'Native American,' while others hate it, and that's OK.

Erik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images

Between "Indian," "Native American," and "First Nations," there are a lot of catch-all terms that are used to describe North America's indigenous residents. I'm often asked, "which one is the right one?"

The honest answer to this question is that it depends. Each of the catch-all terms is going to have fans and detractors.

The way I've grown to understand it is that "Indian" or "American Indian" is an official term. The US government branch that primarily interacts with tribes is called "The Bureau of Indian Affairs." My tribal ID card says "Cowlitz Indian Tribe" in big letters at the top. I don't hear "Indian" said a ton by my Native friends with the general feeling being that "Indians are from India," though sometimes we'll refer to ourselves as Indians, abbreviated to "NDNs" in email chains and text threads because it feels cool.

"Native American" is the term that I use the most in casual conversation, with it often being shortened to just "Native" out of convenience and for cool points. With that in mind, many Natives find the term "Native American" offensive because associating us with "America" feels like rubbing salt in a wound, which, boy, do I get!

"First Nations" is the Canadian term for folks indigenous to Canada. Sometimes people indigenous to the United States will use the term, but it's officially in reference to our friends north of the border.

"Indigenous" is the most "woke" term to use and it works as a great catch-all to describe any groups originally native to a particular location.

If you want to make everyone happy, your best bet is to refer to people by their tribal affiliation. I'm not "Indian," I'm "Cowlitz," for example. That said, I understand that memorizing nearly a thousand tribal affiliations might be a lot to ask when your mind's already full of fun facts about your favorite "Bachelor" contestants. (Did you know that season 23's Colton Underwood used to play football? So interesting!)

And finally, if you want to make me happy, refer to me as Joey Clift. That's my name!

Non-Natives shouldn't call things their 'spirit animal.'

Antonio Perez/ Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

This is less a question and more an observation. I often see people on the internet refer to everything from John Cena to Philadelphia Flyers mascot Gritty as their "spirit animal."

I get it, you like John Cena. I like John Cena too. But for my tribe at least, the process to receive a spirit animal is a hard, personal journey, not unlike receiving a military honor or a Catholic patron sainthood. Don't you think it cheapens a very important cultural achievement for a very marginalized group of people just a little bit when everybody calls everything their "spirit animal?"

If you really need to say that you like or relate to John Cena or Chester Cheetah or any other fictional or non-fictional character, maybe just call them your Patronus instead? A Patronus is from the "Harry Potter" series, and the only person you might offend by using that term is Voldemort.

No one can speak for all Natives — myself included.

David McNew/Getty Images

As I mentioned previously, Native people come in all shapes, sizes, and skin colors, and we're from so many different tribes and cultures that it's impossible for one person to speak for all of us, myself included.

I recently worked in a writers' room with a bunch of super funny Native American comedians, and even within our small room of a half dozen people, our opinions differed on a lot of things. If a room of Native American comedy writers can't speak on all topics with one voice, what makes you think your friend who just got a DNA test that says he's "5% Cherokee" is a good barometer for how all Natives feel about Native American sports mascots, or "Indian princess" Halloween costumes, or wearing a headdress to Coachella, or a million other highly sensitive issues?

(I'm just going to answer that for you. Your friend with the DNA test or your other friend with a mysterious, potentially made-up Cherokee Chief great-great-grandfather who they don't know anything about can't speak for all Natives, either.)

We're still here and we're doing a lot of really awesome stuff.

US Representatives Sharice Davids (L) and Deb Haaland became the first Native American women elected to Congress in 2018. Alastair Pike/AFP via Getty Images

Outside of racist sports mascots and plays about Thanksgiving, Native people are very rarely shown in the media, and almost never in a contemporary light.

Our representation in the media is so lacking in the modern day that we're often called an "invisible" minority. Because of that, a question I often receive from grown adults is, "aren't you guys extinct?"

First off, ouch. Second, no! We're still here. There are around 6 million Native American people currently listed on the US Census, which is similar in size to the Jewish-American population and the Chinese-American population. So we're not exactly "rare" either.

Also, we're doing some amazing stuff! Aaron Yazzie is a genius Navajo mechanical engineer. He's currently working for NASA and he's building drill bits for the 2020 Mars Rover. Rebecca Roanhorse is a stellar Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo author who wrote "Resistance Reborn," an official, canon novel in the "Star Wars" universe. Laguna Pueblo politician Deb Haaland and Ho-Chunk politician Sharice Davids became the first two Native American women elected to US Congress in 2018. Nyla Rose is a tough-as-nails Oneida First Nations professional wrestler signed with All Elite Wrestling. John Herrington is an inspiring Chickasaw Nation astronaut and the first-ever Native American in space.

These are just a few of the many, many very awesome contemporary examples of Natives not just existing, but flourishing in the 21st century. Not only do we still exist, we're killing it.

by Joey Clift