The Neuroscience Of Organizational Culture

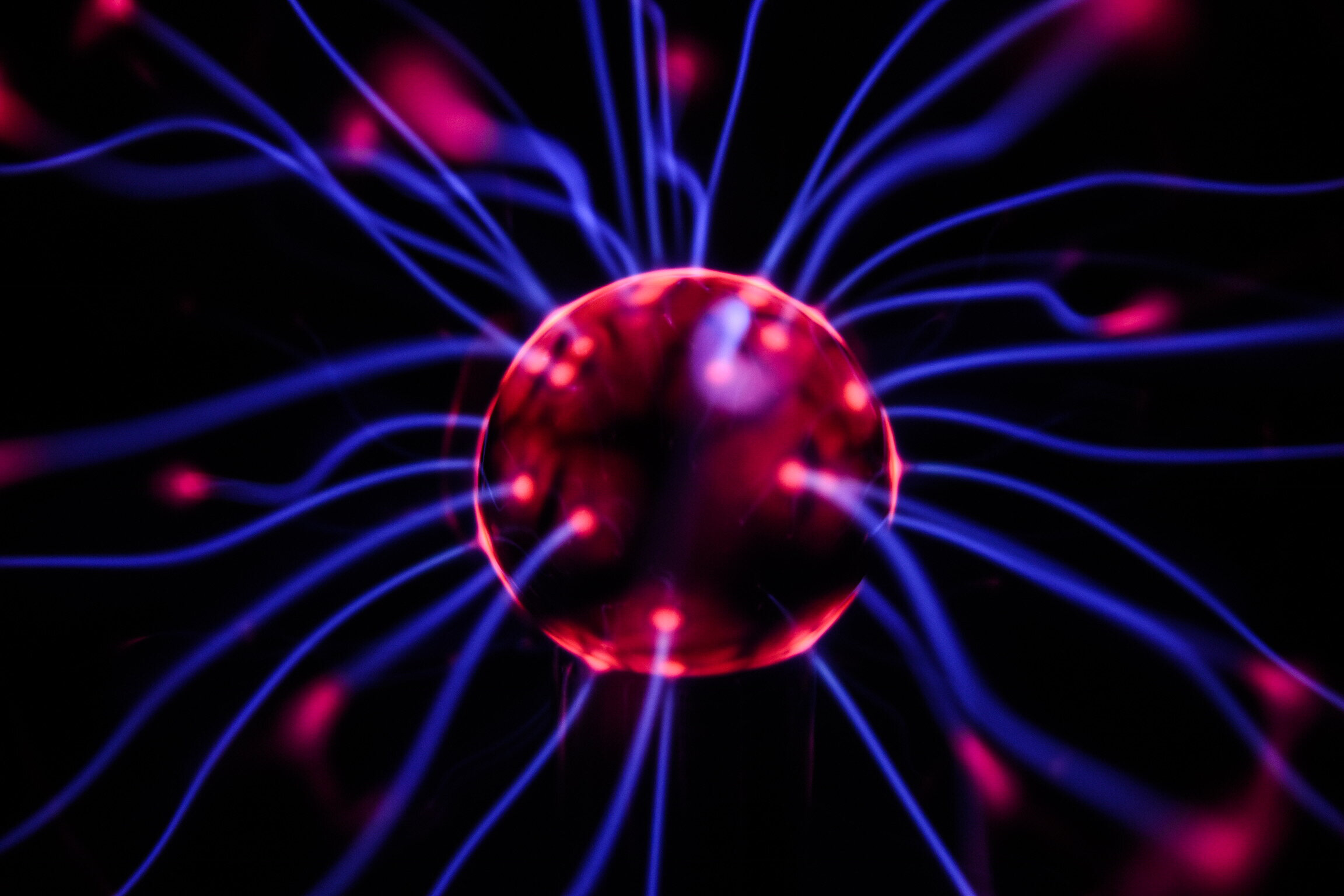

Doidge continues his description by noting that research into neuroplasticity shows that every sustained activity ever mapped – including physical activities, sensory activities, learning, thinking and imagining – changes the brain and the mind in some way. Cultural ideas, rituals, and customs are no exception. As culture evolves so this, when continued and practiced for long enough, creates physical changes in the brain. The neural connections and networks, as well as the strength of those networks (in other words the connections between neurons) become more extensive. In societies, this process may take decades and centuries to occur. In companies, this process may take years and decades. What Doidge’s perspective suggests about the observation of corporate fear I described in the introduction of this essay, is that over time employees’ brains become more likely to expect danger in every interaction, or as Robert Sapolski (2004), the Stanford Neuroscientist, humorously comments as “seeing lions attacking around every bush on the African savanna” – or in the case in our workplaces.

Doidge provides a few fascinating examples of brain “rewiring” that occurs in both societal as well as in business/industry situations. He notes that brain scans of London taxi drivers show that the more years the cabbies spend navigating the streets of London, the larger the volume of the hippocampus, the location of the brain that processes spatial information. Similarly, musicians have several areas of the brain that are larger than non-musicians, for example the structures connecting the two hemispheres. A remarkable societal example that Doidge describes about how brains change in response to cultural activities, are the Sea Gypsies located in the tropical islands of the Burmese archipelago. What differentiates this group is their ability to see underwater at great depths as they search for clams and sea cucumbers. These individuals “learn” to constrict their pupils to see underwater, which is an example of how the nervous systems adapts to experience and training.

Neuroplasticity In The Workplace

But Doidge notes that there is a negative or “dark side” to brain plasticity. He comments that “cultural activities change brain structure” and this can be either good or bad. In the context of corporate culture, this can be bad if companies are unaware of how corporate values, rituals and ways of thinking and behaving create plastic changes in the brains of employees over time. The rewiring of neurons and networks can become difficult to “rewire” when corporate culture needs to change in response to strategic and competitive pressure. In the case of the organization I referenced in the introduction to this essay, the danger with this “hardwiring” of a limbic-driven fear response in organizations suggests that over many years employee’s brains have become acutely trained to be fearful and cautious.