Well you would say that: the science behind our everyday biases

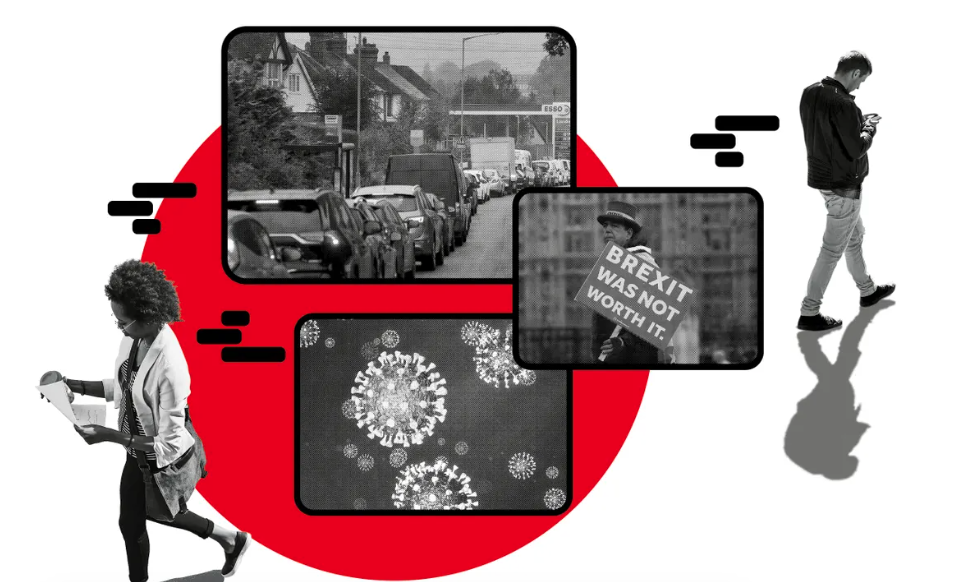

As I wasted an hour’s worth of petrol trying to find more petrol last month, Justin Webb poked at the chief secretary to the Treasury, Simon Clarke, on the Today programme, seeking a reason why much of the country is running on fumes and why HGV drivers are currently more elusive than dark matter. Clarke explained that the problem is “driven in part by workforce demographics” – no doubt – and is “worsened by Covid restrictions”. Agreed. “And worsened by Brexit,” Webb helpfully chipped in. “That’s just a fact.”

But no, Clarke was having none of it. “Well, no. It’s not a fact.”

Unedifying is perhaps the best way to describe these encounters and, like most normal people, I found myself wondering: “Does he really, honestly think this or is this just politicking?”

Well, I can’t answer this question, but we might charitably assume that this dogmatic block is sincere, even if it isn’t right, and Clarke is falling prey to one of the many cognitive biases that skew our ability to see the world objectively. Psychologists refer to this one as “belief perserverance”. Emotional investment in an argument or a belief is a powerful drug and our minds are not predisposed to abandoning that commitment, especially when challenged. This couples well with another cognitive bias called “opinion polarisation”: when presented with evidence that counters your view, you opt to double down and believe your original opinion with even more zeal. These are the mental traps that permeate our public discourse in these strange, polarised times. The evidence that vaccines work and that masks prevent transmission of Covid is robust, yet for many, the psychological costs of taking an opposing view are too great for them to climb out of their wrong hole, so they feel they might as well keep digging.

Humans come preloaded with a host of psychological glitches and physical limits that hinder our ability to see objective reality and nudge us towards a version of the world – and ourselves – that is at best only partly accurate. Objective reality is where we live, but we experience it exclusively in the pitch-black recesses of our skulls. Inside that dark space, we construct a useful version of reality, a kind of controlled hallucination of the world we inhabit. Our senses do the job required of them in building that picture, but are inherently limited: we see only a fraction of the electromagnetic spectrum; bees, birds and reindeer can see in ultraviolet, but we simply do not have the visual hardware to perceive these wavelengths of light. We hear in frequencies somewhere between 20 and 20,000Hz, which means we can’t detect the ultra-bass that elephants can hear over vast distances, nor the ultrasonic squeaks that bats use to chatter and hunt. Humans are literally deaf to much of the living world.

We invented science to identify and bypass these strictures, physical and psychological, so that we can understand the world as it is, rather than how we perceive it to be. The fact that we are aware of these bugs is the first step in addressing them, like an alcoholic admitting that they have a problem. But it doesn’t stop us from falling foul of them with ease.

The Dunning-Kruger effect often skips merrily along with belief perseverance. This is the tendency of non-experts to confidently overestimate their abilities or knowledge on any particular subject. A 2018 study showed that the less people knew about autism, the more likely they were to believe their knowledge exceeded that of doctors. Troublingly, the WHO has said that Covid “has been accompanied by a massive infodemic”, with Dunning-Kruger a key element in misinformation spreading. In April this year, a survey of more than 2,000 participants tested the relationship between knowledge of Covid and confidence in that knowledge. The results showed that a superior sense of confidence correlated with lower levels of knowledge. Charles Darwin spotted this in 1871: “Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.”

Declinism is another persistent fallacy that poisons popular discourse. Very simply, everything in the past was better and everything is getting worse. It wasn’t. It isn’t. Almost everything was significantly less pleasant in the past, for almost everyone. We have had it pretty rough in the past couple of years with a pandemic that has killed millions, but it’s nothing compared with the flu pandemic of 1918. Or the Black Death, in which half of all Europeans died horribly of the plague.

Perhaps the most well-studied psychological malfunction is confirmation bias – the very human tendency to affirm views that reinforce our preconceptions and ignore those that challenge them. Watching and reading most of the media is an exercise in confirming our biases. You’re reading this in the Observer, not the Telegraph or the Sun, so the chances are you may well think Simon Clarke is wrong and the current emptiness of the supermarket shelves and petrol pumps is definitely a result of Brexit. But if you voted for Brexit, you may well think it’s the naughty BBC up to its old tricks. We seek out news sources that tend to support our prejudices and it takes fortitude and effort to pursue politics and opinion with which we disagree. The advent of social media, though, turned the echo chambers of traditional news into booming, cavernous spaces that not just affirm our prior beliefs, but exploit them, amplify them and send us hurtling down confirmation-bias rabbit holes.

Who remembers “hands, face, space”? Boris Johnson’s attempt to remind us to wash our hands, wear masks and maintain social distancing was a noble attempt to employ the “rhyme-as-reason effect”. Statements or instructions that rhyme stick in the memory and therefore are often perceived as being truer. “An apple a day keeps the doctor away” is a false statement that surely was dreamed up by the apple marketing board. In the murder trial of OJ Simpson, where an infamous ill-fitting glove was a crucial piece of evidence presented to the jury, they were told “if it doesn’t fit, you must acquit”. It didn’t and they did. (Note: Theresa May’s staggeringly meaningless phrase “Brexit means Brexit” is excluded from this bias, as rhyming a word with itself does not count.)

By carefully applying scientific methods to studying ourselves, at least we know that all these glitches are there, traps in our minds waiting to be sprung. There’s one other worth mentioning, a meta-bias to cap it all off. It’s called “bias blind spot”: the inability to spot your own biases, coupled with a readiness to identify them perfectly well in others. I definitely don’t have this one at all. But you almost certainly do.