How Private Schools Are Handling Race in 2021

One day last spring, while chitchatting with other moms at the private elementary school their children all attended in Los Angeles, Mimi (her name has been changed) learned about a video that had been shown in her daughter’s first-grade class. Intended to help kids understand the racial unrest sparked by George Floyd’s death, the film, which was made by the educational company BrainPOP, was a five-minute lesson in structural racism. An animated character walked viewers through the civil rights movement and the deaths of Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other Black individuals at the hands of police.

According to Mimi, it was the latest example of how the school had developed a “fetish with race,” which included “blasting out emails about Asian hate crimes” and pushing an anti-bias curriculum into all aspects of the classroom. She and her husband had been excited to get their child into the $31,000-a-year school—a feeder to top high schools—but the video was a breaking point. “Diversity is great,” she says, “but all this is doing is making these kids feel different from each other.”

Mimi contacted administrators at the school, who listened to her objections and then sent out a letter to all first-grade families saying that there had been “concern” among parents and explaining that the school took its diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) direction from organizations teaching racial equality like Pollyanna and Learning for Justice. For Mimi—coming off a year already strained by Zoom school—it wasn’t enough. She pulled her daughter out.

Welcome to a conflagration that has been raging in the country’s most prestigious independent schools for well over a year, ever since the explosion of the Black Lives Matter movement. It mirrors a larger battle about race and school curricula playing out across the nation (Texas, Tennessee, Oklahoma, Iowa, Idaho, and Florida all just ostensibly outlawed the teaching of Critical Race Theory in public schools) that arose after protests over Floyd’s murder. The clash inside private schools may affect far fewer students, but because it has unfolded on a much faster timeline (private schools, after all, do not need to answer to state school boards and can enact their own policy and curriculum changes), it has become a study in how changes in the name of DEI are actually being felt by parents and students, making the discussion less abstract. It also offers a rare glimpse behind the closed doors of institutions accustomed to operating far from the public gaze.

The subject broke onto the national scene over the summer of 2020, when Black alumni and students used Instagram accounts like Black@Brearley and Black@Dalton to recount incidences of racial discrimination and microaggressions they had experienced at their schools. Those schools, along with places like New York’s Trinity and Grace Church and, in Los Angeles, Harvard-Westlake and Brentwood School, responded with intensified DEI programs and other anti-racism initiatives. This, in turn, ignited a backlash from some parents. Then, over this past summer, parents in New York hired trucks to park outside Brearley, Dalton, and Trinity with billboards that read, “WOKE SCHOOL? SPEAK OUT.”

Battles over ideology have long existed in higher education, but the arrival of this charged debate at the secondary level has left people at both ends of the spectrum shellshocked. Educators—many of whom profess liberal ideals—find themselves accused of running racist institutions, while certain white parents feel that their schools have pulled a “bait and switch” on them. Caught in the middle are Black families who question whether beefing up a DEI department or taking a few books off the curriculum will lead to meaningful change. Lisa Johnson, a mother at Campbell Hall, a tony K-12 school in Los Angeles, and the head of Private School Village, an organization that provides resources to Black families at private schools, says she is wary of “performative gestures” that she’s seeing at some schools. “They’re saying they’re going to do stuff and then not having the intention to do it authentically. There’s the town hall meeting—‘Let’s just listen’—and that’s the end of it.”

It is into this environment that students are returning to their gleaming campuses this fall, marking the first time they will be together in person for any sustained amount of time in more than a year. Their parents, meanwhile, will suddenly be brought together in drop-off and pickup lines, and on the sidelines at soccer games—a situation many hope will improve relations. (“It’s a lot easier to lob criticisms when you’re not running into people,” says one mother.)

It will be a return to a semblance of normality, but parents and kids will be entering institutions that are undergoing both everyday and systemic changes. “A lot more students’ eyes have been opened. A lot more people who didn’t really care about [race issues] before are more sensitive,” says Monaco Greene, a junior at Campbell Hall who started a Change.org petition to lobby for mandatory education in institutional racism in schools. (The petition received more than 30,000 signatures.) One parent says he is just hoping for peace. “My attitude is, ‘Hey, look, the curriculum has changed.’ But it’s been an insane 18 months, so obviously things have changed. Everyone needs to take a deep breath.”

But even if tensions settle, America’s private schools are facing a greater challenge. Long before the racial flare-ups of the last year, these institutions have been grappling with the dilemma of embodying traditions that favor privilege and elitism at a time when those systems are facing increased scrutiny. As one parent put it, “When the words equity and inclusion are thrown all over the place, top private schools cannot justify why they exist.”

"It’s a lot easier to lob criticisms when you’re not running into people in person.”

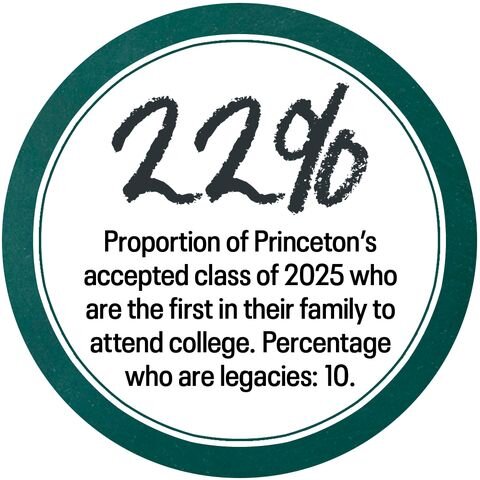

This perception comes as top colleges are accepting record numbers of first-gen and low-income students (20.7 percent of the freshman class at Harvard this fall are first-generation students, and 20.4 percent qualify for Pell Grants—all time highs in both categories). Throw in the dismantling of Advanced Placement courses at many independent schools (another cause of angst for parents dreaming of Ivy League acceptance letters), and Covid-19 and the fraught effect it has had on parents, students, and faculty, and private schools are finding their long-running system in a state of flux. “If you talk to families who spent a lot of money to send their kid to a private high school, especially this last year, there’s a lot of disappointment,” says Sara Harberson, the author of Soundbite: The Admissions Secret that Gets You into College and Beyond. College acceptance results, she says, “are not nearly as strong as they used to be.” That’s particularly true at second-tier schools. But even name brand independent schools are no longer sending 20 kids off to places like Penn in one season, as was the norm 10 years ago. Now half that number is a high-water mark.

“The thing about diversity,” says Shamus Khan, a professor of sociology and American studies at Princeton and the author of Privilege: The Making of an Adolescent Elite at St. Paul’s School, “is that there’s a lot of literature about how diverse organizations make better decisions and have better outcomes. But what people don’t talk about is how diverse institutions are much more contentious. The very aim of that diversification is to increase the range of perspectives.” In other words, there was no way that private high schools’ pivot toward greater inclusivity was going to be painless—particularly as it unfolds at breakneck speed with little input from parents, who often view themselves as high-paying customers.

Indeed, there has been discomfort on all sides as to just how quickly some schools have changed course. While it took California four years to implement the nation’s first statewide ethnic studies curriculum in high schools (the legislation was passed this year), private schools tore up their playbooks “totally overnight,” says Collette Bowers Zinn, the founder and executive director of Private School Axis, an organization that helps Black families navigate the private school journey. “Taking the curriculum that stood for many years and replacing it with things that schools think are diverse—diverse authors and diverse perspectives—I’m for that. But it should be done in a timely process that brings people into the conversation, so they’re not shocked and they can express their fears and trepidations and have them addressed.”

According to the experts I spoke to, people who, like Mimi, pulled their children out of school are exceptions. Even parents who are frustrated by their private schools’ new direction are keeping their kids enrolled, unsure of where else to go and eager for continuity in their kids’ lives following the disruption of Covid-19. They also don’t want to ruffle feathers at institutions they see as stepping stones to the Ivy League. “They have their eye on the prize,” says Mimi. “They don’t want to risk having the school not advocate for them when it’s time to apply to college.”

Emily Glickman, president of Abacus Guide Educational Consulting in New York City, says this sentiment may be particularly true at top schools. “If your child is at Trinity, Dalton, Brearley, or Collegiate, it’s much harder for parents to give up those spaces,” she says. “While there is increased concern among many parents about more politicized curricula [at those schools], in many cases they’re willing to put up with it because they see elite private schools as being helpful in their children’s journey.”

One group whose voices are beginning to emerge are the parents and students who fall in the middle of the woke/anti-woke debate. “My kids aren’t saying, ‘I’m hurting for not reading Beowulf,’ ” one mother told me. “The Catcher in the Rye is still on the book list, as is Death of a Salesman. The canon of Western literature is still alive and well.”

Thomas Schramm, who graduated from Harvard-Westlake last spring, believes the woke/anti-woke debate is “more of a parent problem than a student problem. Parents who didn’t necessarily know what was being taught, or who didn’t understand what was being taught, reached their own conclusions,” Schramm says. “A lot of this is students who are on Zoom at home, their parents are in the same room with them, and they’re hearing a lot of this information that’s being taught to their kids, and they might not get the full context of what’s going on.”

Along those lines, Shamus Khan urges all sides in the private school debate to consider a bigger picture. “The more profound changes are happening in public education, with the legislative agenda being pushed in a range of states right now that basically forbids teaching anything about racism. Private school parents are screaming about critical thinking and free speech, and yet we’re going to have tens of millions of young people educated today who will not be told about the history of white supremacy in America.”

As families settle into the new normal of the fall semester, the unhappy ones will continue to vent behind closed doors, but schools are moving ahead, announcing the official launches of their “multiyear DEI strategic plans,” as is advertised on the Brentwood School website, which now has a page dedicated to its “DEI Initiative.” With no state school board to report to, and parents who have yet to figure out alternate ways to funnel their children into top colleges, private schools—for now, anyway—have the upper hand. As Mike Riera, head of Brentwood, told parents last spring on Zoom, “When families push back more, at some point you have to ask the question: ‘The school’s moving in this direction. Is this really the right school for you?’ Because if you’re going to push back against curriculum in a consistent way, then it’s probably not a good fit.”