Rethinking racial stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination

Racial stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination reflect the human tendencies to conceptualize and value certain configurations of phenotypic features differently, and act on these thoughts and feelings in our interactions with members of racial categories.

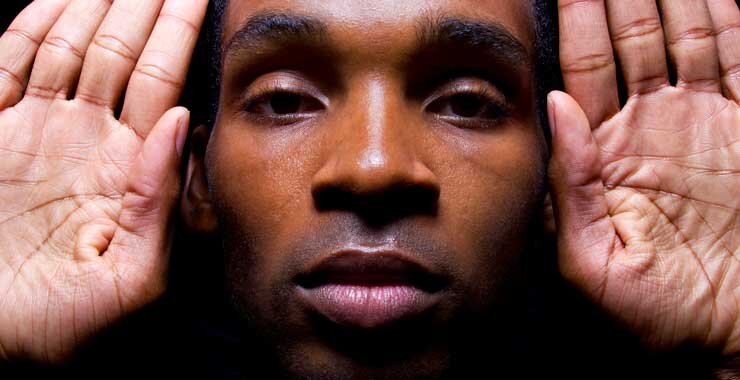

Racial categorization reflects the process of placing people into distinct groups based on variation in phenotypic physical features of the face and body such as skin color, hair color and texture, eye shape, nose width, and lip fullness. Racial stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination reflect the human tendencies to conceptualize and value certain configurations of phenotypic features differently, and act on these thoughts and feelings in our interactions with members of racial categories. Many of us, particularly students of prejudice, can recruit from memory vivid examples of racial bias and its consequences. In both overt and subtle forms, stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination exhibited among individuals belonging to different racial categories has long been a significant source of social strife in American society and abroad. In general, individuals with physical features associated with Whites (lighter skin color, lighter and straighter hair, rounder eyes, narrower nose, thinner lips) are advantaged compared to individuals with features associated with other racial categories.

Rethinking Racial Bias

Notice that the statement ending the previous section is subtly, yet importantly, distinct from the statement that Whites are advantaged over individuals from other racial categories. It reflects another variety of racial bias that occurs both between and within racial categories by suggesting that individuals may possess features associated with Whites and enjoy relatively advantaged status over others without necessarily being categorized as White. At first glance, this concept may seem illogical. How can one conceptualize racial bias, characterized by between-category distinctions, that occurs within a racial category? Our impediment may stem from the well-studied tendency to perceive homogeneity in the characteristics of a target group once categorization has occurred (Tajfel & Wilkes, 1963). In fact, there is as much phenotypic (and genotypic) variability within human populations associated with racial categories as there is between those categories (American Association of Physical Anthropologists, 1996). Thus, this bias can be conceptualized as "racial" because it is appears to be based on the phenotypic characteristics we use to categorize others as a function of race.

This within-category variety of racial bias, while perhaps much less familiar to many observers, has consequences paralleling those of "traditional' racial bias. A relatively small but growing literature produced by historical, sociological, medical, anthropological and psychological researchers confirms that racially-motivated biases exist not only between members of different racial groups, but also among individuals who belong to the same racial group. Most of the focus has been on perceptions of Black Americans by Blacks and Whites as a function of a single feature, skin tone. Early historical evidence suggests that both Blacks and Whites exhibited bias based on skin tone as early as the slavery era (Drake & Cayton, 1945). White European facial features in Blacks were seen as evidence of White ancestry, leading to inferences of racial superiority (Russell, Wilson, & Hall, 1992). In the post-slavery era, lighter skin provided better social, educational, and economic opportunities (Neal & Wilson, 1989). Sociological evidence corroborates these historical data, suggesting that these social disparities persist among Black Americans (Keith & Herring, 1991). Furthermore, medical evidence suggests that darker skin tone is associated with negative health outcomes (Gleiberman, Harburg, Frone, Russell, & Cooper, 1995). These disparities are not limited to Blacks in the United States. The tendency to make discriminations based on skin tone emerges among Latinos in the United States and Latin America (Murguia & Telles, 1996; Uhlmann, Dasgupta, Elgueta, Greenwald, & Swanson, 2002), in Brazil (Harris, Consorte, Lang, & Byrne, 1993), Canada (Sahay & Piran, 1997), India (Beteille, 1967), Israel (Munitz, Priel, & Henik, 1985), Jamaica (Tidrick, 1973), Japan (Goldberg, 1973; Wagatsuma, 1967), Northern Africa (Brown, 1967), and South Africa (Legum, 1967). Evidence suggests that, in each of these societies, lighter skin is generally valued over darker skin, and a person's skin tone has broad implications for his or her relative social status.

These outcomes are, in part, due to interpersonal processes that were not generally recognized in social psychological theory. Dominant theories in social psychology have emphasized the role of racial categories. Few considered phenotypic variation within a racial category as a meaningful factor in representations, judgments, and treatment of others (Maddox, 2004). The mainstream perspectives asserts that, regardless of phenotypic appearance, an individual categorized as a members of a particular group is potentially subject to the full brunt of associated stereotypes and prejudices (Secord, 1958). More recent social psychological evidence has linked within-race variation in phenotypic appearance of Blacks to categorization and stereotype content (Maddox & Gray, 2002), the application of stereotypes and prejudice (Blair, Judd, Sadler, & Jenkins, 2002), and implicit and explicit evaluations (Livingston, 2001; Livingston & Brewer, 2002). This evidence suggests that it would benefit researchers to reconsider the extent to which racial phenotypicality that may elicit categorical thinking and the conditions under which categorical thinking may be accompanied by more nuanced patterns of thought and action.

Racial Phenotypicality Bias

Among psychologists, this general phenomenon has been described using a variety of terms: Afrocentric bias (Blair et al., 2002), the bleaching syndrome (Hall, 1994), colorism (Okazawa-Rey, Robinson, & Ward, 1987), perceptual prejudice (Livingston & Brewer, 2002), phenotyping (Codina & Montalvo, 1994), skin color bias (Hall, 1998), skin tone bias (Maddox & Gray, 2002), and subgroup prejudice (Uhlmann et al., 2002). Each of these terms reflects differential attitudes, beliefs, and treatment of individuals based on variation in phenotypic characteristics of the face traditionally associated with membership in particular racial categories. In previous work, I have offered a rudimentary model of racial phenotypicality bias, a term that corrals the various terms offered by researchers (Maddox, 2004). The model is guided by evidence of our implicit and explicit sensitivity to variation in racial phenotypic appearance among members of the same racial category. The model incorporates suggested revisions to traditional models of person perception (Blair et al., 2002; Maddox & Gray, 2002; Zebrowitz, 1996). Processing begins with identification of a person's physical attributes that act as cues to salient category dimensions such as age, sex, and race. At this stage, the nature of feature processing diverges into two routes of information processing that operate simultaneously and largely independently.

The category-based route. The first is a category-based route as proposed by Maddox & Gray (2002) based on traditional approaches to social representation and judgment (Brewer, 1988; Fiske & Neuberg, 1990). Through this route, processing of the target's phenotypic features results in racial categorization, based on a single, salient feature (e.g., skin tone) or a global assessment of multiple features (Blair et al., 2002; Livingston & Brewer, 2002). At this point, the individual may be placed into a relevant subcategory as a function of racial phenotypicality (e.g., light-skinned or dark-skinned) depending on the perceiver's conceptual framework. Only salient subcategory representations may guide the process of categorization. Subcategory use is more or less likely depending on person characteristics or contextual cues present in the judgment context (Maddox & Chase, 2004). In that study, the use of skin tone-based subcategories of Blacks was augmented through a manipulation that made salient learned distinctions between light- and dark-skinned Blacks. Once fit between the target and (sub) category membership is established, associated stereotypes or prejudices (Maddox & Gray, 2002) may be used in interpersonal judgments.

The feature-based route. The second route is feature-based; influencing social perception apart from the traditional range of category-based processing. This route employs direct associations between phenotypic features and stereotypic traits (Blair et al., 2002) or prejudices (Livingston & Brewer, 2002). These associations may be learned over time, or reflect innate knowledge of social information that may be overgeneralized to other individuals with similar features (Zebrowitz, 1996). An important aspect of this route is that phenotype continues to influence target judgments in situations even when racial categorization overrides within-race variation through the category-based route (Blair et al., 2002). Furthermore the information that features convey will be applied regardless of the target's racial category membership (Blair et al., 2002; Secord, 1958; Zebrowitz, 1996) and is less subject to conscious control (Blair, Chapleau, & Judd, 2005).

The role of conceptual knowledge. The model also recognizes varieties of conceptual knowledge that may guide the processing of target attributes through both the category-based route and the feature-based route. Possibilities include metaphorical associations with various colors (Secord, 1958), early childhood experiences with light and dark (Williams, Boswell, & Best, 1975), essentialist beliefs (Haslam, Rothschild, & Ernst, 2002), implicit causal theories (Medin & Ortony, 1989), cultural standards of physical attractiveness (Breland, 1998), and beliefs about the relationship between physical features and personality (Livingston, 2001). Each of these and others may contribute to category-based and/or feature-based judgments.

Why Rethink Racial Bias?

This re-conceptualization does not maintain that the study of categorical thinking in the domain of race is obsolete. At times, racial categorization may very well override the significance of within-category variability. However, there are a number of developing factors in our society that will increase the significance of racial phenotypicality (Maddox & Dukes, 2006). First, is the growing phenotypic diversity among the population attributed to increasing numbers of immigrants of color (Massey, 2002) as well as increasing rates of interracial marriages (Steven & Tyler, 2002) and multiracial births (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1992). Second, is the recent debate over the inclusion of a multiracial category option in the U.S. Census, highlighting the growing recognition that people who may appear to belong to a particular racial category may identify with multiple categories (Steven & Tyler, 2002). Finally, consider the continuing debate surrounding the idea that race is a biological certainty. A growing body of evidence indicates that the biological nature of race is a myth. In fact, racial categories and their apparent correlates arise as a function of social construction processes (American Anthropological Association, 1998; American Association of Physical Anthropologists, 1996).

The confluence of these factors suggests that more and more people in the country will not fit into traditional models of racial stereotyping and prejudice, augmented by the deterioration of the traditional framework surrounding race. These factors may lead to decreased reliance on race in social perception and judgment and, perhaps, and increased reliance on racial phenotype. If we are to recognize the face of stereotyping and prejudice in the future, it is vitally important that researchers give greater consideration to the role of racial phenotype and conceptual knowledge in social judgment.