How to Promote Racial Equity in the Workplace

Intractable as it seems, the problem of racism in the workplace can be effectively addressed with the right information, incentives, and investment. Corporate leaders may not be able to change the world, but they can certainly change their world. Organizations are relatively small, autonomous entities that afford leaders a high level of control over cultural norms and procedural rules, making them ideal places to develop policies and practices that promote racial equity. In this article, I’ll offer a practical road map for making profound and sustainable progress toward that goal.

I’ve devoted much of my academic career to the study of diversity, leadership, and social justice, and over the years I’ve consulted on these topics with scores of Fortune 500 companies, federal agencies, nonprofits, and municipalities. Often, these organizations have called me in because they are in crisis and suffering—they just want a quick fix to stop the pain. But that’s akin to asking a physician to write a prescription without first understanding the patient’s underlying health condition. Enduring, long-term solutions usually require more than just a pill. Organizations and societies alike must resist the impulse to seek immediate relief for the symptoms, and instead focus on the disease. Otherwise they run the risk of a recurring ailment.

To effectively address racism in your organization, it’s important to first build consensus around whether there is a problem (most likely, there is) and, if so, what it is and where it comes from. If many of your employees do not believe that racism against people of color exists in the organization, or if feedback is rising through various communication channels showing that Whites feel that they are the real victims of discrimination, then diversity initiatives will be perceived as the problem, not the solution. This is one of the reasons such initiatives are frequently met with resentment and resistance, often by mid-level managers. Beliefs, not reality, are what determine how employees respond to efforts taken to increase equity. So, the first step is getting everyone on the same page as to what the reality is and why it is a problem for the organization.

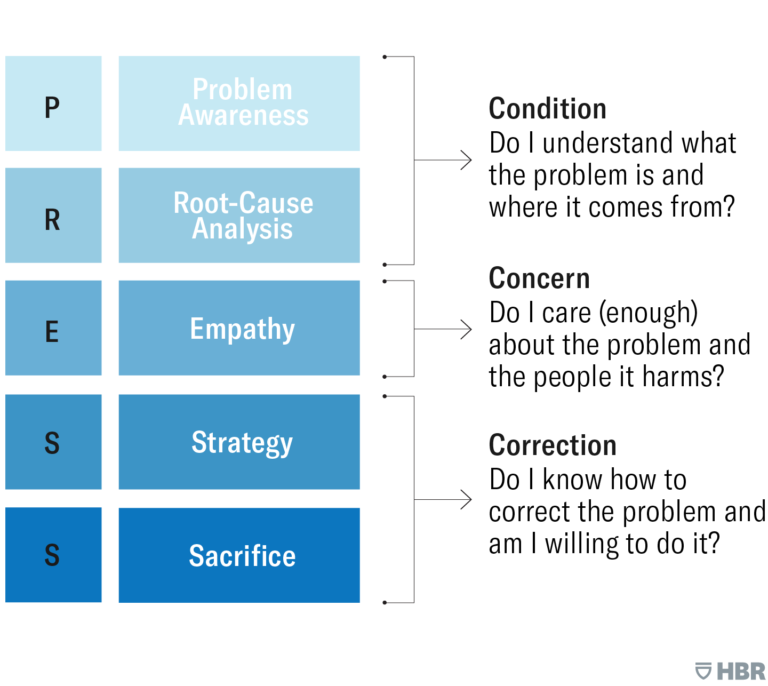

But there’s much more to the job than just raising awareness. Effective interventions involve many stages, which I’ve incorporated into a model I call PRESS. The stages, which organizations must move through sequentially, are: (1) Problem awareness, (2) Root-cause analysis, (3) Empathy, or level of concern about the problem and the people it afflicts, (4) Strategies for addressing the problem, and (5) Sacrifice, or willingness to invest the time, energy, and resources necessary for strategy implementation. Organizations going through these stages move from understanding the underlying condition, to developing genuine concern, to focusing on correction.

Let’s now have a closer look at these stages and examine how each informs, at a practical level, the process of working toward racial equity.

Problem Awareness

To a lot of people, it may seem obvious that racism continues to oppress people of color. Yet research consistently reveals that many Whites don’t see it that way. For example, a 2011 study by Michael Norton and Sam Sommers found that on the whole, Whites in the United States believe that systemic anti-Black racism has steadily decreased over the past 50 years—and that systemic anti-White racism (an implausibility in the United States) has steadily increased over the same time frame. The result: As a group, Whites believe that there is more racism against them than against Blacks. Other recent surveys echo Sommers and Norton’s findings, one revealing, for example, that 57% of all Whites and 66% of working-class Whites consider discrimination against Whites to be as big a problem as discrimination against Blacks and other people of color. These beliefs are important, because they can undermine an organization’s efforts to address racism by weakening support for diversity policies. (Interestingly, surveys taken since the George Floyd murder indicate an increase in perceptions of systemic racism among Whites. But it’s too soon to tell whether those surveys reflect a permanent shift or a temporary uptick in awareness.)

Even managers who recognize racism in society often fail to see it in their own organizations. For example, one senior executive told me, “We don’t have any discriminatory policies in our company.” However, it is important to recognize that even seemingly “race neutral” policies can enable discrimination. Other executives point to their organizations’ commitment to diversity as evidence for the absence of racial discrimination. “Our firm really values diversity and making this a welcoming and inclusive place for everybody to work,” another leader remarked.

The real challenge for organizations is not figuring out “What can we do?” but rather “Are we willing to do it?”

Despite these beliefs, many studies in the 21st century have documented that racial discrimination is prevalent in the workplace, and that organizations with strong commitments to diversity are no less likely to discriminate. In fact, research by Cheryl Kaiser and colleagues has demonstrated that the presence of diversity values and structures can actually make matters worse, by lulling an organization into complacency and making Blacks and ethnic minorities more likely to be ignored or harshly treated when they raise valid concerns about racism.

Many White people deny the existence of racism against people of color because they assume that racism is defined by deliberate actions motivated by malice and hatred. However, racism can occur without conscious awareness or intent. When defined simply as differential evaluation or treatment based solely on race, regardless of intent, racism occurs far more frequently than most White people suspect. Let’s look at a few examples.

In a well-publicized résumé study by the economists Marianne Bertrand and Sendhil Mullainathan, applicants with White-sounding names (such as Emily Walsh) received, on average, 50% more callbacks for interviews than equally qualified applicants with Black-sounding names (such as Lakisha Washington). The researchers estimated that just being White conferred the same benefit as an additional eight years of work experience—a dramatic head start over equally qualified Black candidates.

Research shows that people of color are well-aware of these discriminatory tendencies and sometimes try to counteract them by masking their race. A 2016 study by Sonia Kang and colleagues found that 31% of the Black professionals and 40% of the Asian professionals they interviewed admitted to “Whitening” their résumés, either by adopting a less “ethnic” name or omitting extracurricular experiences (a college club membership, for instance) that might reveal their racial identities.

These findings raise another question: Does Whitening a résumé actually benefit Black and Asian applicants, or does it disadvantage them when applying to organizations seeking to increase diversity? In a follow-up experiment, Kang and her colleagues sent Whitened and non-Whitened résumés of Black or Asian applicants to 1,600 real-world job postings across various industries and geographical areas in the United States. Half of these job postings were from companies that expressed a strong desire to seek diverse candidates. They found that Whitening résumés by altering names and extracurricular experiences increased the callback rate from 10% to nearly 26% for Blacks, and from about 12% to 21% for Asians. What’s particularly unsettling is that a company’s stated commitment to diversity failed to diminish this preference for Whitened résumés.

A Road Map for Racial Equity

Organizations move through these stages sequentially, first establishing an understanding of the underlying condition, then developing genuine concern, and finally focusing on correcting the problem.

This is a very small sample of the many studies that have confirmed the prevalence of racism in the workplace, all of which underscore the fact that people’s beliefs and biases must be recognized and addressed as the first step toward progress. Although some leaders acknowledge systemic racism in their organizations and can skip step one, many may need to be convinced that racism persists, despite their “race neutral” policies or pro-diversity statements.

Root-Cause Analysis

Understanding an ailment’s roots is critical to choosing the best remedy. Racism can have many psychological sources—cognitive biases, personality characteristics, ideological worldviews, psychological insecurity, perceived threat, or a need for power and ego enhancement. But most racism is the result of structural factors—established laws, institutional practices, and cultural norms. Many of these causes do not involve malicious intent. Nonetheless, managers often misattribute workplace discrimination to the character of individual actors—the so-called bad apples—rather than to broader structural factors. As a result, they roll out trainings to “fix” employees while dedicating relatively little attention to what may be a toxic organizational culture, for example. It is much easier to pinpoint and blame individuals when problems arise. When police departments face crises related to racism, the knee-jerk response is to fire the officers involved or replace the police chief, rather than examining how the culture licenses, or even encourages, discriminatory behavior.

Appealing to circumstances beyond one’s control is another way to exonerate deeply embedded cultural or institutional practices that are responsible for racial disparities. For example, an oceanographic organization I worked with attributed its lack of racial diversity to an insurmountable pipeline problem. “There just aren’t any Black people out there studying the migration patterns of the humpback whale,” one leader commented. Most leaders were unaware of the National Association of Black Scuba Divers, an organization boasting thousands of members, or of Hampton University, a historically Black college on the Chesapeake Bay, which awards bachelor’s degrees in marine and environmental science. Both were entities that could source Black candidates for the job, especially given that the organization only needed to fill dozens, not thousands, of openings.

Diana Ejaita

A Fortune 500 company I worked with cited similar pipeline problems. Closer examination revealed, however, that the real culprit was the culture-based practice of promoting leaders from within the organization—which already had low diversity—rather than conducting a broader industry-wide search when leadership positions became available. The larger lesson here is that an organization’s lack of diversity is often tied to inadequate recruitment efforts rather than an empty pipeline. Progress requires a deeper diagnosis of the routine practices that drive the outcomes leaders wish to change.

To help managers and employees understand how being embedded within a biased system can unwittingly influence outcomes and behaviors, I like to ask them to imagine being fish in a stream. In that stream, a current exerts force on everything in the water, moving it downstream. That current is analogous to systemic racism. If you do nothing—just float—the current will carry you along with it, whether you’re aware of it or not. If you actively discriminate by swimming with the current, you will be propelled faster. In both cases, the current takes you in the same direction. From this perspective, racism has less to do with what’s in your heart or mind and more to do with how your actions or inactions amplify or enable the systemic dynamics already in place.

Workplace discrimination often comes from well-educated, well-intentioned, open-minded, kindhearted people who are just floating along, severely underestimating the tug of the prevailing current on their actions, positions, and outcomes. Anti-racism requires swimming against that current, like a salmon making its way upstream. It demands much more effort, courage, and determination than simply going with the flow.

In short, organizations must be mindful of the “current,” or the structural dynamics that permeate the system, not just the “fish,” or individual actors that operate within it.

Empathy

Once people are aware of the problem and its underlying causes, the next question is whether they care enough to do something about it. There is a difference between sympathy and empathy. Many White people experience sympathy, or pity, when they witness racism. But what’s more likely to lead to action in confronting the problem is empathy—experiencing the same hurt and anger that people of color are feeling. People of color want solidarity—and social justice—not sympathy, which simply quiets the symptoms while perpetuating the disease.

If your employees don’t believe that racism exists in the company, then diversity initiatives will be perceived as the problem, not the solution.

One way to increase empathy is through exposure and education. The video of George Floyd’s murder exposed people to the ugly reality of racism in a visceral, protracted, and undeniable way. Similarly, in the 1960s, northern Whites witnessed innocent Black protesters being beaten with batons and blasted with fire hoses on television. What best prompts people in an organization to register concern about racism in their midst, I’ve found, are the moments when their non-White coworkers share vivid, detailed accounts of the negative impact that racism has on their lives. Managers can raise awareness and empathy through psychologically safe listening sessions—for employees who want to share their experiences, without feeling obligated to do so—supplemented by education and experiences that provide historical and scientific evidence of the persistence of racism.

For example, I spoke with Mike Kaufmann, CEO of Cardinal Health—the 16th largest corporation in America—who credited a visit to the Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, in Montgomery, Alabama as a pivotal moment for the company. While diversity and inclusion initiatives have been a priority for Mike and his leadership team for well over a decade, their focus and conversations related to racial inclusion increased significantly during 2019. As he expressed to me, “Some Americans think when slavery ended in the 1860s that African Americans have had an equal opportunity ever since. That’s just not true. Institutional systemic racism is still very much alive today; it’s never gone away.” Kaufmann is planning a comprehensive education program, which will include a trip for executives and other employees to visit the museum, because he is convinced that the experience will change hearts, open eyes, and drive action and behavioral change.

Empathy is critical for making progress toward racial equity because it affects whether individuals or organizations take any action and if so, what kind of action they take. There are at least four ways to respond to racism: join in and add to the injury, ignore it and mind your own business, experience sympathy and bake cookies for the victim, or experience empathic outrage and take measures to promote equal justice. The personal values of individual employees and the core values of the organization are two factors that affect which actions are undertaken.

Strategy

After the foundation has been laid, it’s finally time for the “what do we do about it” stage. Most actionable strategies for change address three distinct but interconnected categories: personal attitudes, informal cultural norms, and formal institutional policies.

To most effectively combat discrimination in the workplace, leaders should consider how they can run interventions on all three of these fronts simultaneously. Focusing only on one is likely to be ineffective and could even backfire. For example, implementing institutional diversity policies without any attempt to create buy-in from employees is likely to produce a backlash. Likewise, focusing just on changing attitudes without also establishing institutional policies that hold people accountable for their decisions and actions may generate little behavioral change among those who don’t agree with the policies. Establishing an anti-racist organizational culture, tied to core values and modeled by behavior from the CEO and other top leaders at the company, can influence both individual attitudes and institutional policies.

Just as there is no shortage of effective strategies for losing weight or promoting environmental sustainability, there are ample strategies for reducing racial bias at the individual, cultural, and institutional levels. The hard part is getting people to actually adopt them. Even the best strategies are worthless without implementation.

Fairness requires treating people equitably—which may entail treating people differently, but in a way that makes sense.

I’ll discuss how to increase commitment to execution in the final section. But before I do, I want to give a specific example of an institutional strategy that works. It comes from Massport, a public organization that owns Boston Logan International Airport and commercial lots worth billions of dollars. When its leaders decided they wanted to increase diversity and inclusion in real estate development in Boston’s booming Seaport District, they decided to leverage their land to do it. Massport’s leaders made formal changes to the selection criteria determining who is awarded lucrative contracts to build and operate hotels and other large commercial buildings on their parcels. In addition to evaluating three traditional criteria—the developer’s experience and financial capital, Massport’s revenue potential, and the project’s architectural design—they added a fourth criterion called “comprehensive diversity and inclusion,” which accounted for 25% of the proposal’s overall score, the same as the other three. This forced developers not only to think more deeply about how to create diversity but also to go out and do it. Similarly, organizations can integrate diversity and inclusion into managers’ scorecards for raises and promotions—if they think it’s important enough. I’ve found that the real barrier to diversity is not figuring out “What can we do?” but rather “Are we willing to do it?”

Sacrifice

Many organizations that desire greater diversity, equity, and inclusion may not be willing to invest the time, energy, resources, and commitment necessary to make it happen. Actions are often inhibited by the assumption that achieving one desired goal requires sacrificing another desired goal. But that’s not always the case. Although nothing worth having is completely free, racial equity often costs less than people may assume. Seemingly conflicting goals or competing commitments are often relatively easy to reconcile—once the underlying assumptions have been identified.

As a society, are we sacrificing public safety and social order when police routinely treat people of color with compassion and respect? No. In fact, it’s possible that kinder policing will actually increase public safety. Famously, the city of Camden, New Jersey, witnessed a 40% drop in violent crime after it reformed its police department, in 2012, and put a much greater emphasis on community policing.

The assumptions of sacrifice have enormous implications for the hiring and promotion of diverse talent, for at least two reasons. First, people often assume that increasing diversity means sacrificing principles of fairness and merit, because it requires giving “special” favors to people of color rather than treating everyone the same. But take a look at the scene below. Which of the two scenarios appears more “fair,” the one on the left or the one on the right?

Diana Ejaita

People often assume that fairness means treating everyone equally, or exactly the same—in this case, giving each person one crate of the same size. In reality, fairness requires treating people equitably—which may entail treating people differently, but in a way that makes sense. If you chose the scenario on the right, then you subscribe to the notion that fairness can require treating people differently in a sensible way.

Of course, what is “sensible” depends on the context and the perceiver. Does it make sense for someone with a physical disability to have a parking space closer to a building? Is it fair for new parents to have six weeks of paid leave to be able to care for their baby? Is it right to allow active-duty military personnel to board an airplane early to express gratitude for their service? My answer is yes to all three questions, but not everyone will agree. For this reason, equity presents a greater challenge to gaining consensus than equality. In the first panel of the fence scenario, everybody gets the same number of crates. That’s a simple solution. But is it fair?

In thinking about fairness in the context of American society, leaders must consider the unlevel playing fields and other barriers that exist—provided they are aware of systemic racism. They must also have the courage to make difficult or controversial calls. For example, it might make sense to have an employee resource group for Black employees but not White employees. Fair outcomes may require a process of treating people differently. To be clear, different treatment is not the same as “special” treatment—the latter is tied to favoritism, not equity.

There is no test or interview that can invariably identify the “best candidate.” Instead, hire good people and invest in their potential.

One leader who understands the difference is Maria Klawe, the president of Harvey Mudd College. She concluded that the only way to increase the representation of women in computer science was to treat men and women differently. Men and women tended to have different levels of computing experience prior to entering college—different levels of experience, not intelligence or potential. Society treats boys and girls differently throughout secondary school—encouraging STEM subjects for boys but liberal arts subjects for girls, creating gaps in experience. To compensate for this gap created by bias in society, the college designed two introductory computer-science tracks—one for students with no computing experience and one for students with some computing experience in high school. The no-experience course tended to be 50% women whereas the some-experience course was predominantly men. By the end of the semester, the students in both courses were on par with one another. Through this and other equity-based interventions, Klawe and her team were able to dramatically increase the representation of women and minority computer-science majors and graduates.

The second assumption many people have is that increasing diversity requires sacrificing high quality and standards. Consider again the fence scenario. All three people have the same height or “potential.” What varies is the level of the field and the fence—apt metaphors for privilege and discrimination, respectively. Because the person on the far left has lower barriers to access, does it make sense to treat the other two people differently to compensate? Do we have an obligation to do so when differences in outcomes are caused by the field and the fence, not someone’s height? Maria Klawe sure thought so. How much human potential is left unrealized within organizations because we do not recognize the barriers that exist?

Finally, it’s important to understand that quality is difficult to measure with precision. There is no test, instrument, survey, or interviewing technique that will enable you to invariably predict who the “best candidate” will be. The NFL draft illustrates the difficulty in predicting future job performance: Despite large scouting departments, plentiful video of prior performance, and extensive tryouts, almost half of first round picks turn out to be busts. This may be true for organizations as well. Research by Sheldon Zedeck and colleagues on corporate hiring processes has found that even the best screening or aptitude tests predict only 25% of intended outcomes, and that candidate quality is better reflected by “statistical bands” rather than a strict rank ordering. This means that there may be absolutely no difference in quality between the candidate who scored first out of 50 people and the candidate who scored eighth.

The big takeaway here is that “sacrifice” may actually involve giving up very little. If we look at people within a band of potential and choose the diverse candidate (for example, number eight) over the top scorer, we haven’t sacrificed quality at all—statistically speaking—even if people’s intuitions lead them to conclude otherwise.

Managers should abandon the notion that a “best candidate” must be found. That kind of search amounts to chasing unicorns. Instead, they should focus on hiring well-qualified people who show good promise, and then should invest time, effort, and resources into helping them reach their potential.

CONCLUSION

The tragedies and protests we have witnessed this year across the United States have increased public awareness and concern about racism as a persistent problem in our society. The question we now must confront is whether, as a nation, we are willing to do the hard work necessary to change widespread attitudes, assumptions, policies, and practices. Unlike society at large, the workplace very often requires contact and cooperation among people from different racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds. Therefore, leaders should host open and candid conversations about how their organizations are doing at each of the five stages of the model—and use their power to press for profound and perennial progress.

A version of this article appeared in the September–October 2020 issue of Harvard Business Review.